|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

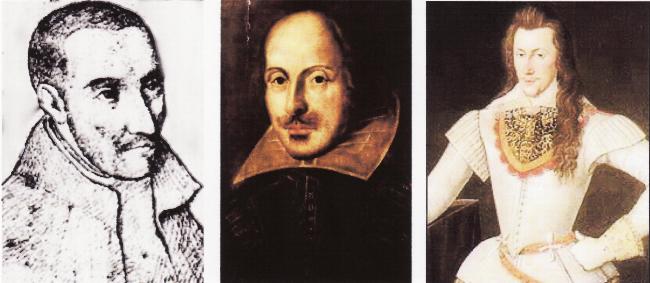

SHAKESPEARE, THE EARL AND THE JESUITJohn Klause |

|||||||||||||

CHAPTER

2

Lucrece There

are many anachronisms in

Shakespeare’s Lucrece. Some of them transport the

world of

medieval

heraldry and knighthood into antique Rome (64, 1694-7). Others place

general

Christian doctrines like “Grace” and the Last Judgment in a pagan

context (712,

924). Still others lend a particularly Catholic slant to ancient Roman

religion, introducing into it palmers and pilgrimages (791), saints,

shrines,

and incense (85, 194), and the sacrament of Penance (“the blackest sin

is

clear’d with absolution” [354]). Some of these (surely deliberate)

historical

solecisms become less puzzling when, like the mention of Catholic

beliefs and

practices in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, they are

read as meant

for a

particular audience. Shakespeare composed Lucrece

in 1593 or

1594 for

Henry Wriothesley, whose sympathetic ties to the Old Faith in which he

was

first raised were to persist into King James’s reign.[1]

“Incense” and “absolution” were as much a part of Shakespeare’s

indirect address

to his patron as was his paraphrastic translation of Southampton’s

motto (Ung

par tout, et tout par ung) in a line spoken by the poem’s

moralizing

narrator: “one for all, or all for one, we gage” (Lucrece,

144).[2] That

Shakespeare wrote A Midsummer Night’s

Dream, as has been suggested, with special reference to the

wedding

of

Southampton’s mother in 1594 and with special meaning for Southamtpon

himself

might help to explain why, despite radical differences in genre and

tone

between poem and play, they share language and imagery. The two works

were

almost contiguous in the author’s mind. We have seen, however, that

Shakespeare’s memory could reach across years for its associations.

Linguistic

parallels do not always confirm chronology, nor does chronology always

provide

reasons for parallelism. There is another explanation for the

correspondences

between the texts, one for which the previous chapter has established

the

ground. Theseus’s

remarks on the tricks played by

imagination--“in the night . . . /

How

easy is a bush suppos’d a bear” (5.1.21-2)--is

echoed in

Lucrece’s

complaint against “Opportunity” and “Time”: Let ghastly shadows his lewd eyes affright, And the dire thought of his committed evil Shape every bush a hideous shapeless devil. (971-3) Both works

refer

to the sinful soul as “spotted” (MND

1.1.110; Luc

721,

1172); both use metaphors of “misgrafting” (MND

1,1,137; Luc

1558) and the rare Shakespearean words “cranny” and “gleam”

(MND

3.1.70, 5.1.158, 163; Luc 310, 1086; MND

5.1.274; Luc

1378);[3]

both

invoke the concept of discordia concors (MND

5.1.60; Luc

1558); and both create word play out of a common antithesis: “A tedious

brief scene” (MND 5.1.56); “My woes are tedious,

though my

words are brief” (Luc 1309).

Theseus’s tongue-tied

“clerks”

shiver

and look pale,

Make periods in the midst of sentences, Throttle their practic’d accent in their fears. . . . (5.1.95-7) They resemble

Lucrece in more than one of her difficulties with speech: Her modest eloquence with sighs is mixed . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . She puts the period often from his place, And midst the sentence . . . her accent breaks. . . . (563-6) But more than “he” her poor tongue would not speak, Till after many accents and delays, Untimely breathings, sick and short assays. . . . (1718-20) We

have noted the blessing given by Oberon

in which he wards off “the blots of nature’s

hand” from

the

married couples’ future “issue”: Never

mole, hare-lip, nor scar

(5.1.411-14)Nor mark prodigious, such as are Despised in nativity, Shall upon their children be It is closely

paralleled in Lucrece’s prophecy of the shame that Tarquin’s children

would

suffer if he should violate her: The blemish . . . will never be forgot, Worse than a slavish wipe, or birth-hour’s blot, For marks descried in men’s nativity Are nature’s faults, not their own infamy. (536-9) For each of

these instances in which

Shakespeare comes close to repeating himself from one work to the

other, there

is a passage in Southwell’s writing that may suggest itself as a source

or

imaginative catalyst, the Jesuit’s words and notions apparently serving

as a

link between poem and play. Such are Southwell’s references to “natures

blots,” to filial scars, wens, and warts and their

Shakespearean

mutations.

We have seen a precedent for Shakespeare’s descriptions of trembling,

tongue-tied oratory in Marie Magdalens Funeral Teares,

and for

his

characterization of deceptive, bush-transforming imagination in Saint

Peters

Complaint. Southwell writes also of the “spotted soul,”

misgrafting,

“crannies,” discordia concors,

and the relief from

tediousness by

brevity.[4]

He

writes, in fact, so much that has gone into the making of Lucrece

that,

as with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the affiliations

ought to be

examined

in detail for their significance. Lucrece herself

appears in The Epistle

of Comfort, her suicide described in terms that Shakespeare

saw fit

to

adopt: “Lucretia,” observes Southwell,

“sheathed

her knife in her owne bowels to renoune her chastitye” (126v);

and he is followed by the poet: “she sheathed in her

harmless

breast / A

harmful knife that thence her soul unsheathed”

(1723-4; cf. R&J

5.3.170). Neither the word “sheathed” nor a Latin equivalent is used in

any

source of Lucretia’s story on which Shakespeare’s passage relies. In

Thomas

Nashe’s The Unfortunate Traveller, the matron

Heraclide, who is

like

Lucrece a victim of rape, commits suicide after addressing her dagger:

“Point,

pierce, enwiden, patiently I afford thee a sheath.”[5]

It is less likely, however, that Shakespeare was here thinking of

Nashe’s tale

(both works were published in 1594 and dedicated to Southampton, and

one writer

might have seen the other’s manuscript) than that Nashe was burlesquing

Shakespeare’s poem, or, since it is probable that Nashe had read the Epistle

of Comfort,[6]

that

both were recalling the same text. It is Shakespeare, after all, who

like

Southwell attributes the “sheathing” to Lucrece; and the poem’s

extensive debt

to Southwell in other respects will tend to confirm his influence in

this case. It has long but

not widely been suspected

that Lucrece owes something to Southwell’s Saint

Peters

Complaint.[7]

That

Shakespeare should have consulted such a poem for help in writing the

extended

passages of “complaint” that appear in his own work is not an

improbable idea.

Southwell’s manuscript was in circulation before the publication of

Samuel

Daniel’s Rosamond (1592), which is supposed to have

reestablished a

vogue for this form in the ’90s and of which Shakespeare made

considerable use.[8]

Commentators have pointed to similar features of style in Lucrece

and

Southwell’s Complaint--”similar antitheses and

apostrophes . .

. , a

common store of similes”[9]--but

have determined that these “only prove that there was a common poetic

currency

in circulation at the time.”[10]

Critics inclined to discern “influence” upon one poet by another lend

more

weight to evidence of “a shared theme and approach.”[11]

This “theme” upon which Lucrece and the Complaint

agree

is said

to be the anatomy of “sin.”[12]

While not in itself vague, this notion is so generally Christian, even

when

conveyed as in Southwell and Shakespeare through a specific metaphor

like the

defilement of a temple-like soul or body (Luc 719,

1172; SPC,

631-3) that in either poem it may point to no other source than St.

Paul: “Know

ye not that ye are the temple of God . . . ? Know ye not that your body

is the

temple of the Holy Ghost . . . ?” (1 Cor. 3:16, 6:19). It is in fact

the verbal

obligation of Shakespeare’s poem to Southwell’s, the extent of which

has never

been appreciated, that more certainly demonstrates influence; and

although

Shakespeare’s themes may arise out of Southwell’s, they are complicated

in ways

that the Jesuit would not have entirely appreciated. The number of

echoes of Saint Peters

Complaint in Lucrece is much too large

to allow anything

like a

complete list of them. The following set of comparisons, however, will

give a

sense of how retentive Shakespeare’s memory was when he read

Southwell’s poem: SPC Lucrece 3: 740: with guilty feares with guilty fear [Sw’s and Ss’s are the first two uses of this rare expression (Chadwyck-Healey)] 5: 279: Remorse, the Pilot Desire my pilot is 6-9: 966: Shipwracke . . . / Shun not the shelfe . . . / I could prevent this storm, and shun Sticke in the sandes / . . . stormes thy wrack; 317: sticks; 335: shelves and sands 13: 1040: Give vent unto the vapours of thy brest, To make more vent for passage of her That thicken breath; 782: let thy misty vapours march so thick 15: 846-49: Where sinne was hatchd, let teares now wash O unlook’d for evil . . . / . . . Why the nest should . . . hateful cuckoos hatch in sparrow’s nests? 18: 1172: thy spotted soule in weeping dewe Her sacred temple spotted; 1829: In . . . dew of lamentations 20-2: 40-41: conscience . . . sting sting / His . . . thoughts 23: 1141: hartes that languish tune our heart-strings to true languishment 26: 798: The monument of feare, the map of shame monuments of . . . moans; 402: the map of death 28: 1638: the infamy of fame My fame, and thy perpetual infamy 50: 351: I left my guide . . . leaving God Then Love and Fortune be my gods, my 57: 158: What trust to one, that truth it selfe defied? Then where is truth, if there be no 69: 603: Soone sowing shames How will thy shame be seeded . . . ? 70-1: 767: Nurcing with teares . . . , / . . . harbinger nurse of blame 85: 867: sowers [n.] sours [n., the only instance in Ss] 87-9: 690: loosing monethes and yeares to gaine new This momentary joy breeds months of pain howers / . . . a moment, all thou hast 91-3: 1151: the maze of countlesse straying wayes one encompass’d with a winding maze . . . / . . . To winde weake senses 97: 19: could I rate so high . . . ? Reck’ning his fortune at such high proud 103-6: 657-58: The mother sea from overflowing deepes, Thy sea within a puddle’s womb is hearsed Sendes foorth her issue by divided vaines: And not the puddle in thy sea dispersed; 649- Yet back her offspring to their mother creepes 51: The petty streams that pay a daily debt / To pay their purest streames with added gaines To their salt sovereign . . . , / Add to his flow 108: 577: Bemyred the giver with returning mud Mud not the fountain that gave drink to thee 122: 762: Whose speeches voyded spight, and thus breathes she forth her spite; breathed gall 889: gall 150: 315: A puffe of womans wind Puffs forth another wind 155: Dedication: but one moietie but a superfluous Moity 166-7: 1330-35: a maidens easie breath being blown with wind of words . . . / Did blow me down and blastmy soule . . . to death blast 175: 849: Fidelitie was flowne when feare was hatched, hateful cuckoos hatch in sparrows’ nests Incompatible brood in vertues nest 200-8: 709-10: with feeble foote . . . sinnes soft stealing pace With . . . strengthless pace, Feeble Desire 232-7: 907: infecting all resort . . . evill advise Advice is sporting while infection breeds 236: 268: Dumme Orator All orators are dumb 242-3: 928: the sinne: / Coatch drawne with many horse sin’s pack-horse 289: 1014: Small gnats Gnats are unnoted 303: 1614: with semblance of excuse my errour guild no excuse can give the fault a mending 314: 1338: two homely droyles [i.e., servants] The homely villain [a servant] 327: 435: [eyes’] chearing raies cheers his burning eye 343-44: 618: have I sweet lessons read, / In those deare Must he in thee read lectures of such shame? eies the registers of truth 765: register . . . of shame 346: 1603: redress’d thy ruth tell thy grief, that we may give redress 366: 1115: sweet are crums where pined thoughts He ten times pines that pines beholding food do starve; 539: It dies for drought yet had a spring in sight 368-70: 1455-58: shadowed things . . . / . . . by being shap’d in the spring that those . . . pipes have fed, those life giving springs [i.e., eyes] On this sad shadow Lucrece spends her eyes And shapes her sorrow 372: 719: in my selfe whom sinne and shame defac’d; his soul’s fair temple is defac’d 632: templed 378-81: 1116-19: You seeing, salve . . . banks To see the salve . . . banks 441-2, 450: 1076-78: Thy eyes . . . / To make my heart gush out a My eyes . . . Shall gush pure streams to weeping loode. . . . purgde purge [only instance of “gush” in Ss] 451: 1611-12: Like solest Swan that swimmes in silent deepe, this pale swan in her watery nest And never sings but obsequies of death Begins the sad dirge of her certain ending 470-7: 1061-64: Ill gotten impes . . . probates of infringed lawes infringed oath; / This bastard graff . . . . . . Bring forth the fruite father of his fruit 480: 872: Sinne did all grace of riper groth devour What virtue breeds iniquity devours 483-6: 836-40: Shed on your hony drops you busie bees . . . , My honey lost, and I, a drone-like bee . . . . Hornets I hyve, salt drops their labour plies, In thy weak hive a wand’ring wasp hath Suckt out of sinne And suck’d the honey which thy 515-16: 1249-52: what cave . . . can conceale In men . . . remain / Cave-keeping evils My monstrous fact . . . 531-4: 813: [for] her child . . . A mothers love . . . The nurse, to still her child is hardly stild 552-562: 71: warre . . . Sweet Roses mixt with Lillies Their silent war of lilies and of roses 580: 1396: Or write my inward feeling in my face The face of either cipher’d either’s heart 385: cyphered [only instance of “cipher’d” in Ss] 584: 799: reeking hellish steeme foul reeking smoke 618: 664-5: Our Cedar now is shrunke into a shrub The cedar stoops not to the base shrub’s But low shrubs wither at the cedar’s root 633-5: 719, 723: But sinne, his temple hath to ruine brought his soul’s fair temple is defaced . . . . . . . . unconsecrate consecrated 636-41: 847: Profaned wretch . . . Ah sinne . . . When virtue is profan’d in such a devil That . . . Angels turnes to Divells 663: 160: till I my selfe confounded When he himself himself confounds 668-70: 597: borrowing lying shapes to maske thy face . . . Hast thou put on his shape to do him shame? A cunning dearly bought with losse of grace 794: mask their brows and hide their infamy; 749: To cloak offenses with a cunning brow 680: 807: All thinges Characters are to spell my fall The light will show, character’d in my brow, The story of sweet chastity’s decay 686-88: 131: paines . . . trafficke by retayle: Despair to gain doth traffic oft for gaining Making each others miseries their gaines 691: 1111: Pleasd with displeasing lot Grief best is pleas’d with grief’s society 715-16: 900: prisoner . . . Chain’d . . . free that soul which wretchedness hath Till grace vouchsafing captive soule to bayle chained; 1725-6: did bail [her soul] from the deep unrest / Of that polluted prison 727-31: 769: [Sleepe,] whisperer of dreames [O Night,] whisp’ring conspirator Creating straunge chymeraes. . . : 450-1: From forth dull sleep by dreadful . . . giving fansie theames, fancy waking, / That thinks she hath beheld To make dumme shewes with worlds of some ghastly sprite. . . . anticke sightes: 474: he by dumb demeanor seeks to show Casting true griefes in fansies forging mold 458-60: there appears / Quick-shifting antics . . . : / Such shadows are the weak brain’s forgeries 759-60: 1248: A worthlesse worme . . . may . . . / the little worms that creep . . . lowly creepe 759: 1399-1400: some milde regard mild glance . . . deep regard 769: 683-4: Prone looke, crost armes modest eyes . . . prone lust; 793: cross their arms To use a

metaphor common to both

poets,

Shakespeare has “suck’d” the essence of Southwell’s poetic language,

recombining the ingredients to produce a new confection. One of his

reasons for

such an intensive reading of the Complaint may have

been that

he

considered Saint Peter’s lengthy, operatic examination of conscience a

promising model for Tarquin’s failed mental attempt at moral rectitude

and for

Lucrece’s tormented meditations. Daniel’s Rosamond

was in some

ways too

temperate a precedent. Southwell’s poem, unlike Lucrece,

has

little

narrative interest, lacks the complication of a narrator-commentator

whose

point of view cannot always be trusted, and is as much a study of

repentance,

which is not an issue in Lucrece, as of remorse.

Yet Peter

luxuriates in

the psychological depths of conscience, even to a desire for death (SPC,

83), and in ways that show heroines of the complaint tradition like

Jane Shore

or Rosamond to be by his baroque standard insensitive and superficial.

Shakespeare would not have missed the opportunities latent in the

Saint’s

example. He made Roman Lucrece an “earthly saint” adored and violated

by the

“devil” Tarquin (Luc, 85), giving both characters

plausible if

extreme

psychic life, and a rhetoric to match. Ah sinne, the nothing that doth all things file: Outcast from heauen, earthes curse, the cause of hell: Parent of death . . . . . . . . . . . . Shot, without noyse: wound without present smart: First, seeming light; proving in fyne a load, Entring with ease, not easily wonne to parte. . . . (SPC, 637-51) Lucrece’s

complaint to “Night”

is similar

in form: O

comfort-killing Night, image of hell!

Dim register and notary of shame! Black stage for tragedies and murders fell, Vast sin-concealing chaos! nurse of blame! Blind muffled bawd! dark harbour for defame, Grim cave of death! whispering conspirator With close-tongued treason and the ravisher! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . O unseen shame! invisible disgrace! O unfelt sore! crest-wounding, private scar! (Luc, 764-70, 827-28) This rhetorical

form was

commonplace in

complaint literature; but Shakespeare filled his template with

Southwell’s

content: not simply with the general notion of guilt as “invisible

disgrace . .

. , unfelt sore” (cf. Southwell’s “wound

without present

smart” [SPC,

649]), and hackneyed thoughts of “sin,” “hell,” and “death,” but with specific words

and images brought

together from different parts of Saint Peter’s Complaint.

Peter’s “registers

of truth” (SPC, 344) turn into Lucrece’s “register

. . .

of shame”;

“Nurcing with teares . . . , harbinger

of blame: Treasons

to wisedom” (language from Peter’s aprostrophe to “rashnesse” [SPC,

67-72]) shades into “nurse of blame . . . harbor

for defame

. . . treason”; the “cave” that,

as Peter knows, cannot

conceal sin

(515-16) suggests the analogy of Night to the “Grim cave

of

death” where

sin is punished; and Peter’s “sleepe,” the lying “whisperer

of

dreames”

(SPC, 727), does its work at night, which is

Lucrece’s “whispering

conspirator.” It was not just

from Southwell’s Peter,

however, that Shakespeare derived inspiration. In the Jesuit’s writings

a

number of other “saints” speak in the mode of complaint, some briefly,

others

at considerable length; and they too have left their mark on Lucrece: a repentant King David,

for instance (in

“Davids Peccavi”); Joseph, the perplexed husband of Mary in “Josephs

Amazement”; the Virgin Mary herself in her sorrowful address “To Christ

on the

Crosse” and in her “Complaint . . . having lost her Sonne in

Jerusalem.” After

Saint Peter, the most voluble of Southwell’s complaining saints is Mary

Magdalen, a heroine who (though not a model of perpetual chastity)

shares with

her Roman counterpart an absolute and self-denying attachment to her

“Lord,”

deep stores of articulate grief, a sovereign disdain for her own life,

and considerable

powers of argument. Marie Magdalens Funeral Teares

appears to

have sat

prominently in the “book and volume” of Shakespeare’s “brain” as he

wrote of a

woman whose “weakness” would turn out to be stronger than the

“strength” of

men. There are numerous verbal parallels between this work and Lucrece.[13]

Indeed, Shakespeare’s poem is rich in such correspondences with many of

Southwell’s lyrics and with his prose.[14]

The most significant inter-textual dialogue between Lucrece

and

Southwell’s controversial writing begins with the Jesuit’s handbook for

martyrs, The Epistle of Comfort. To

Shakespeare’s poem the Epistle

has contributed a clutch of expressions--some of them merely residues

of

memory, and others more significant in that they suggest reasons for

Shakespeare’s

immersion in the writings of an outlaw priest whose unflinching

adherence to

principle put him in the way of martyrdom, which inevitably found him.

The

first kind of recollection is reflected in such parallels as these

(many more

could be added), based on passages found rather close together in

Southwell’s

book: Epistle Lucrece 63r: 719-23: battering downe the walles, the defacinge of his soul’s fair temple is defaced, of . . . the temple . . . . . . . . . . . . . batter’d down her consecrated wall 67r-v: 1042: consumed . . . Ætna . . . smoake . . . ayre As smoke from Aetna, that in air consumes 67v: 592: the very rockes . . . dissolved For stones dissolv’d to water do convert 72r: 777: a huge Chaos [is hell] Vast sin-concealing chaos 74v: 703-4: he shall vomitt out the riches which he hath Drunken Desire must vomit his receipt devoured . . . abhominable; 73r: dronckerdes; Ere he can see his own abomination 55v: receyte 75v: 725-6, 731: ther death ever liveth . . . alwayes healed to thrall / To living death be new wounded . . . . . . . . . . the wound that nothing healeth 82v: 335-6: Pirates sett lightes in the shallow places, rocks, high winds, strong pirates, shelves and hidden rockes and sands 86v: Argument 45: changes of the state of Rome, from . . . the state government changed from kings Kinges . . . to Consuls to consuls In considering

such parallels,

we might

observe that Shakespeare has assimilated language from Southwell in a

number of

different ways. Since the Jesuit often repeats himself, it is likely

that mere

iteration would lodge certain expressions in his reader’s acutely

receptive

mind: as “double death” (in “Life is but losse,” 24; Funeral

Teares,

33v; EC, 33r

), leading to “double death” in Lucrece,

1114;

or, “Remorse, the

Pilot,” “Christ for

your Pilott,” (SPC, 5; EC, 96v),

anticipating

“Desire

my pilot” in Lucrece, 279). Sometimes Shakespeare’s

language

combines

(for reasons that only imagination can “know” or chance “explain”)

elements

derived from different parts of his Southwellian “sources”: “the dead

of night,

/ When. . . / No

comfortable star

did lend his light” (Lucrece, 162-4) may derive, for

example,

both from

the Funeral Teares’ “no star of hope”

(58v,

with “comfortable”

appearing a few pages later) and the Epistle of Comfort’s

“in

the darke,

and mistye night, every light .

. . is comfortable”

(3v).

There are also occasions on which Shakespeare’s recollection of

Southwell

intrudes upon his use of another source. A good example lies at the end

of the

prose “Argument” prefatory to Lucrece, when, in

following his

classical

sources, Shakespeare (and the writer of the Argument does

seem

to be the

poet, not an editor)[15]

observes that after the banishment of the Tarquins, “the state

government changed

from kings to consuls.” Of these sources, the closest in

wording to

Shakespeare’s version is that of Painter, who translated Livy thus:

“The raigne

of the kings from the first foundation of the Citie continued CCXLIV

yeares.

After which governmente two Consuls were appointed. . . .”[16]

Although in The Epistle of Comfort Southwell’s

description of

the same

political phenomenon was only obliquely related to his main point about

the

nobility of the cause for which a martyr suffers, his language is

closer to

Shakespeare’s than is Painter’s: “changes of the state

of Rome, from

. . . Kinges . . . to Consuls” (86v).

It is conceivable

that

Shakespeare at times made special note of certain images used by

Southwell,

taking them over for his own ends because he considered them simply

“striking.”

Perhaps that is why he had Lucrece refer to her body as “bark

.

.

.pill’d away” from her soul (1169), inspired by Southwell’s reference

to the

human body as the “bark and rind of a man” (Epistle

unto his

Father,

6) and his description of a tempest that peeled away even the “barke of

trees”

(EC, 66r; see also “Loves

Garden grief,” 19-21). And

there

were times when Shakespeare seemed to mark out (at least mentally) a

whole

passage that was ripe for conceptual if not verbal appropriation (cf. EC,

147v-48r [with Funeral

Teares, A8r]

and Lucrece, 204-110).[17]

But

on the whole, the vast obligation of one poet to the other can hardly

be

explained by attempts to find occasions or purposes for every local

example of

it. Shakespeare did not “go” to Southwell’s works for help in

appareling the

child of his invention. Lucrece was already within

them,

waiting to be

born, impatient, even for delivery. The truth of

this claim will be understood

in attending to a second kind of presence of the Epistle of

Comfort

in

Shakespeare’s poem, the language of sacrifice and martyrdom that helped

to make Lucrece the “graver labor” promised to the

earl of

Southampton in the

dedication to Venus and Adonis. One reason why Lucrece

is more

“serious” than its predecessor is that religious issues lie more

conspicuously

at the center of the poet’s concern; Southampton’s religious crisis is

more

directly acknowledged and spoken to, and in a way that more searchingly

explores its depths. Shakespeare again makes use of Southwell to

suggest the

challenges faced by the young Catholic nobleman, whose religious

position,

already described in some detail, must now be elaborated on. A biographer of

Southampton, noting the

remark of a contemporary of the earl that the peer “carried his

business

closely and slily,” has found “little reason to doubt that Southampton

had

early learned to banish candour from certain regions of his life.”[18]

One

of those “regions” was certainly religion, about which Tudor and Stuart

governments

forced many of their subjects to be silent or to dissemble. It is

wholly

natural, then, to find evasiveness in the answer that Southampton, when

on

trial for his part in the Essex conspiracy, gave to Attorney-General

Coke, who

had charged him with being a “papist”: “where as you charge me to be a

Papist,

I protest most unfainedly that I was never conversant with any of that

sort

only I knew one [Wright] a Priest of that sort that went up and dowen

the towen

but I never conversed with him in all my lief.”[19]

The earl does not directly answer the charge, the gist of his answer

being only

that he is no party to Catholic plots--as might be undertaken by

“papists” in a

narrowly defined sense.[20]

No

one at the trial was unaware of his family’s deep and in some cases

continuing

loyalty to Catholicism. Some were aware that he had, in fact, known

more of

Thomas Wright than he let on. Wright was a former Jesuit who in 1595

had come

to England as a secular priest under the protection of Essex (and much

against

the wishes of Burghley), proposing that Catholics consistently submit

to the

government and unite in opposition to Spain in return for the freedom

to

practice their religion.[21]

He

was more than once the guest of Essex; and if Southampton never

“conversed”

with Wright (who dedicated the 1604 edition of his treatise The

Passions of

the Mind to Southampton), he must have been privy to the

exchanges

that the

priest had had with his host. Essex attracted to himself many Catholic

followers by holding out to them the prospect of toleration.

Southampton

himself may have shared that hope. According to G.

P. V. Akrigg, however,

Southampton did not need the benefits of toleration, at least for

himself. The

biographer surmised that the young earl was already on his way to

Protestantism

while at Cambridge (1585-9), and that he hid his altered convictions

from his

Catholic relations and friends for as long as he could.[22]

Akrigg emphasized that Southampton publicly denied “papist” connections

at his

trial in 1601, and that in 1604 he was actually the recipient of

recusancy

fines, ostensibly deriving financial benefit from the very penal

statutes under

which his father had suffered. There is, however, no substantial

evidence about

Wriothesley’s beliefs, religious or otherwise, while he was at

Cambridge.[23]

His

public disavowal of papistry was hardly unequivocal. And his

biographers have

failed to see that he probably collected the recusancy fines in order

to return

them. Among the recusants “granted” to Southampton were William Copley,

John

Shelley, and Edward Gage of Bentley.[24]

Gage, an attorney, had been close to the second earl, who had made him

an

executor of his will, and had in fact played a major role not only in

untangling the perplexities of the late earl’s estate, but in resolving

the

younger Wriothesley’s financial difficulties.[25]

The three recusants were themselves kinsmen (and all of them kinsmen of

Robert

Southwell) and were through various marriages related to Southampton.[26]

Since it is known that at least on two occasions Southampton took

nominal

possession of the forfeited estates of Catholic families to protect

them from

the law’s depredations,[27]

it

is quite likely that he played in these cases the same kind of game

with the

fines.[28]

It

is true that he finally conformed (and probably from an early date) to

the laws

of church attendance (even his mother had disapproved of his youthful

non-conformity in this matter)[29]

and

accepted other ecclesiastical requirements of the state church. As a

young man

he took arms against Catholic Spain, on the “Islands Voyage” of 1597,

and in

his middle and later years favored a “Protestant” foreign policy for

the

Continent (as, in fact, did many nationalistic Catholic Englishmen).[30]

An

early eighteenth-century witness reported that Southampton had been

“converted

from Popery” by Sir Edwin Sandys in King James’s reign.[31]

Yet early in 1605, “above two hundredeth [sic] pounds worth

of popish bookes” were

“taken

about Southampton house and burned in Poules Churchyard.”[32] At about this time the

earl seems to have

been involved with his brother-in-law Thomas Arundel in a scheme to

establish a

colony in America that would serve as a refuge for English Catholics.[33]

In

1606, a minister was jailed for “unfitting speeches about

Southampton”--speeches

which probably complained of the earl’s Catholic sympathies.[34]

In

1613, a recusant named John Cotton, who lived in one of Southampton’s

manors in

Hampshire, was suspected of having written a pamphlet, Balaam’s

Ass,

that called King James the Antichrist. When a warrant was issued for

his arrest

on charges of treason, he fled for asylum to Southampton House, where

many “of

Cotton’s co-religionists were still to be found.”[35]

The earl could hardly do anything but turn him in to the authorities,

and

Cotton spent six years in the Tower before being acquitted. At the time

of his

arrest, Cotton gave his age as fifty-three years.[36]

It seems probable that this was the same John Cotton who left England

in 1576

for a Jesuit school in Belgium in the company of his kinsman and coeval

Robert

Southwell, for he identified himself at the time of his surrender as

having

been “at Douai,” and that his “kinsman, Mr. Anthony Copley”

(Southwell’s

cousin) had told him of Balaam’s Ass.[37]

(This Cotton, then, would have been a son of George Cotton, cousin of

Bridget Copley,

Robert’s mother, and related to Southampton through the Gages.)[38]

John returned from the Continent to become a “country squire”; Robert

became a

Jesuit and slipped into England using the alias “Mr. Cotton.”[39] In his “closeness” and “slyness,” then, Southampton lived for a long time in divided worlds; he could not and clearly did not wish to sever his attachments to his Catholic family and acquaintances after accommodating himself, whether out of conviction or prudent calculation, to Protestant principalities and powers. But this conclusion is hardly momentous. It does not suggest whether or how his conscience played a role in decisions and actions. Because of his taciturnity on religious subjects, the soundings taken of his religious mind have always been, by necessity, rudimentary and shallow; and so perhaps they will forever remain. These explorations should not be left where they have rested, however, without considering that a most “Catholic” poem, Lucrece, lifted for him by his poet out of the thought-world of a Jesuit, has much to say about the principles that a man of sensitive mind, entering a new phase of his life, may have faced in deciding whether to be, or not to be, what the heroine of the poem calls herself: a martyr (802). In 1594, when Lucrece

was published, priests were still, according to government reports,

lodging and

gathering in and near Southampton House;[40]

but the dangers to Catholics from government persecution seemed

destined to

become ever more severe. Parliament in the previous year had taken up,

at the

insistence of the government, a bill that, as it affected the recusant

laity,

“exceeded in its ferocity all previous anti-Catholic laws.”[41]

The intention was to add new punishments to the already heavy fines for

recusancy (twenty pounds for each four-week period) and to create new

capital

penalties for such “treasonous” actions as coming into England as a

priest,

harboring or helping such priests, or being reconciled to the Catholic

Church

by them. Under the

proposed law, the

refusal to attend church would make the recusant liable to the seizure

of all

his goods and the profits of two-thirds of his estates; rescusants

would be

barred from leasing, renting, or selling land; recusant women would

lose their

dowries; a man who married a recusant heiress would forfeit two-thirds

of her

inheritance; Catholics could no longer hold any public office or belong

to a

learned profession; one who kept a recusant guest or servant would be

liable to

a fine of ten pounds a month; children of recusant parents would be

taken from

them at age seven and educated as Protestants. The legislation was not

enacted,

and instead, a much less onerous law was passed, requiring that

recusants

remain within five miles of their homes or forfeit goods and income.[42]

The

new threats to their well-being, however, must have clarified as never

before

to many Catholics how much they might have to suffer in the name of

conscience

if the voices of their more rigorous pastors were not tempered in

demanding

resistance to the ungodly laws of an heretical regime. As if in

anticipation of

wavering and doubt among the faithful, the Jesuit Henry Garnet

published in

1593 three documents aimed at strengthening the resolution of those who

might

bend or break in the face of an increasing terror: A Treatise

of

Christian

Renunciation; An Apology against the Defence of

Schisme;

and A

Declaration of the Fathers (which presented a version of the

Council of

Trent’s declaration in 1562 against schism). Garnet was at pains to

confute in

his writings the tracts written by Thomas Bell, a Lancashire priest

(and later

apostate), who had defended attendance at church, giving public

expression to a

casuistry that priests sometimes saw fit to offer humanely to their

penitents

in the privacy of confession.[43]

Lay

Catholics, then, were not always sure that they had a vocation to

martyrdom,

but some of their “ghostly fathers” were quite clear on the point. One

of the

clearest had been Garnet’s now imprisoned fellow-Jesuit, Robert

Southwell. Saint Peters

Complaint, so ubiquitously present in

Shakespeare’s Lucrece,

was written by Southwell with candid designs upon a specific kind of

reader:

the English Catholic whose loyalty to the Church had lapsed, or was

about to.

The poem’s speaker is the “Rock” upon whom Christ had professed to

“build his

church” (Matt. 16:18), but who was blown over, as the poem says, by “a

puffe of

womans wind,” “a maidens easie breath” (150, 167). The maiden in

question was,

in John’s gospel (18:17), the high priest’s portress, who while Jesus

was being

interviewed before his crucifixion charged Peter with being one of his

disciples, eliciting the first of the apostle’s three denials of his

Lord. In

Southwell’s England, the maid was of course Elizabeth, whose

proclamations

(“breath”) pressured many into schism or apostasy, which was the denial

of

their Lord and his truth unto the “death” of their souls (168). Peter

would not

find “excuse” for his fall in the examples of David, Solomon, and

Samson, who

had suffered their “vertue, wisedome, [and] strength” to be by “woemen

spild”

(301-3). He had succumbed not to feminine beauty, but to “fear” which a

woman’s

voice inspired (307-16)--a fear not of force, so he claimed, but (as

the

unheroic Falstaff would put it) of “A word. . . . Air.” Southwell and

his

Catholic readers were all too aware, of course, that Elizabeth’s words

were

backed by force of arms, by pursuivants and the collectors of fines, by

the

rack, the gibbet, the knife, and the axe. Indeed, after his complaint,

Peter

would fully repent and, a victim of force, later be crucified. But Saint

Peters Complaint was a poem composed by a man who risked

martyrdom

daily

out of a sense of the absoluteness of his truth and its sometimes

scandalously

brutal demands (“If any man come to mee, and hate not his father, and

mother,

and wife, and children, and brethren, and sisters: yea, and his own

life also,

he cannot be my disciple” [Luke 14:26]). It was addressed to Christians

who

should be made to see that the powers and treasures of this world were

trivial

or illusory. For a martyr, the words of a persecutor are but “air,”

which would

destroy a soul only if the soul were to give it the power to do so.

Such was

Southwell’s message as well to his father in the sternly reproachful Epistle

that Shakespeare remembered as he wrote Lucrece. Your present estate is in danger of the deepest harms if you do not the sooner recover yourself into the fold and family of God’s Church. What have you gotten by being so long customer to the world but false ware, suitable to the shop of such a merchant whose traffic is toil, whose wealth trash, and whose gain misery . . . ? It cannot be fear that leadeth you amiss, seeing it were too unfitting a thing that the cravant cowardice of flesh and blood should daunt the prowess of an intelligent person, who by his wisdom cannot but discern how much more cause there is to fear God than man, and to stand in more awe of perpetual than of temporal penalties (EF, 12). This same theme

is exhaustively and at times wearisomely elaborated in the Epistle

of

Comfort, as some of the book’s chapter headings indicate: we

are moved to suffer tribulation willinglye, both by the president of

Christ,

and the title of a Christian. . . . tribulation best agreeth with the estate, and conditions of our life. . . . the cause we suffer for is the true Catholicke fayth. . . . the estate of the persecuted in a good cause is honourable. . . . death in itself to the good, is comfortable. . . . Martyrdome is glorious in it selfe, most profitable to the Church and honourable to the Martyrs . . . (2 r-v). Behind these

conclusions are principles

that make Lucretia, not one of the Epistle’s

heroines (she

killed

herself, says Southwell, for the vain purpose of bringing “renoune” to

her “chastytie”),

but one of many “examples” permitted by God in the world for the

“exhortation”

of those whom he has asked to suffer for a better cause (126v-127r).

John Donne would argue “paradoxically” in Biathanatos

(1608)

and more

ingenuously in Pseudo-Martyr (1610) against both

the ancient

and

contemporary Roman cults of martyrdom. But Shakespeare does not argue;

he

dramatizes, and in a way that leaves the issues on both sides of the

controversy as inexorably ambiguous as the certitudes of the

antagonists are

fierce. The ambiguities

in Lucrece have been

appreciated from different perspectives, but most readers who worry

over the

poem’s enigmas consider them rooted in “psycho-social” and “moral”

issues.[44]

The

heroine herself has been criticized as verbose, passive, compliant with

an

oppressive patriarchy, psychologically and morally confused, and even,

despite

her victimization, immoral. She has also been regarded as eloquent,

consummately brave and independent, divided and tormented in ways that

make her

hugely sympathetic, and, despite her questionable self-slaughter, a

moral

paragon.[45]

Both kinds of judgments of Lucrece may mingle in the same reader’s

response.

And at least one commentator, Ian Donaldson, has sensed that in the

drawing of

contradictions “the central moral complexities of the story are in some

ways

curiously evaded. . . . There is a wavering between different criteria

of

judgment, a sense that Shakespeare, while sharing some of his

contemporaries’

doubts about the way in which Lucrece chose to act, is attempting--not

altogether successfully--to retell Lucrece’s story in a manner which is

by and

large approbatory.” It is especially the “alternation between Roman and

Christian viewpoints” that creates confusion.[46]

By Christian standards (such as those of St. Augustine, whose moral

condemnation of Lucrece is frequently referred to in commentary on the

poem)[47]

Lucrece is right to doubt the virtue

of

suicide: To

live or die which of the twain were better,

When life is sham’d and death reproach’s debtor. “To kill myself,” quoth she, “alack what were it, But with my body my poor soul’s pollution? (1154-7) And by these

same

standards, she is wrong to take her life for any of the reasons she

offers for

doing so: a feeling of stain or defilement--”let it not be call’d

impiety, / If

in this blemish’d fort I make some hole / Through which I may convey

this

troubled soul” (1174-6); a compulsion for revenge against her

assailant--“My

stained blood to Tarquin I’ll bequeath, / Which

by him tainted shall for him be spent . . . / How

Tarquin

must be us’d,

read it in me” (1181-95); or a concern for honor: “’Tis honor to

deprive

dishonor’d life, / The one will live, the other being dead. / So of

shame’s

ashes shall my fame be bred. . . .” (1186-8). If Lucrece were allowed

to abide

in her own world, a “Roman” ethic might easily exculpate her from

“Christian”

faults, and readers who want reasons to offer her sympathy and

admiration might

do so on historicist grounds. But Shakespeare does not allow her to

live in the

Rome of Livy or Ovid, where the thoughts and actions of a simpler

character

might make perfect moral sense. She is forced (and Tarquin with her) to

probe

her tender conscience for marks not only of Roman “disgrace” and

“shame” (751,

756), but of Christian “guilt” and “sin” (754, 753), in the knowledge

that her

body and soul were to be “kept” in their purity not only for her

husband, but

for “heaven” (1163-6). This is not really an “alternation” of

perspectives, as

Donaldson says, but (as he more accurately puts it without noting the

difference in meaning between the terms) a “fusion.”[48]

Whether this commingling is an evasive resort, a failure to “take moral

repossession of the older story [and to charge] it with new depth and

intricacy

of significance,”[49]

remains, however, to be seen. A

seventeenth-century reader of Thomas

Heywood’s play The Rape of Lucrece (published in

1608) wrote at

the end

of the text he had read a comment about the heroine’s final action: . . .

though some men commend this act Lucretian

She shewd herself in’t (for all that) no good Christian Nay ev’n those men that seeme to make the best ont Call her a Papish good, not good Protestant.[50] Whatever this

reader’s reasons for considering Lucrece “Papish,” Shakespeare

anticipated

them, for his Catholic sources baptized his pagan ones, not just by

steeping

the poem in their language, but by helping it speak to the plight of

Elizabethan “Romans” (like the earl of Southampton) who stood between a

temporal power that would “rape” their consciences and a spiritual

authority

that would have them resist such violence unto martyrdom. Shakespeare’s

Catholic readers probably

would not have recognized the specific literary connections between

Southwell’s

works and Lucrece. They would not have been aware

that St.

Peter’s refusal

of martyrdom (in St Peters Complaint) or Richard

Southwell’s

apostasy

(in An Epistle unto his Father) or Robert

Southwell’s

complaints against

the government’s persecutions of Catholics for their religion (in An

Humble

Supplication to her Majestie) or the Jesuit’s exhortations to

martyrs and

celebration of martyrdom (in An Epistle of Comfort)

all lurked

behind

the poem in the author’s mind. They would have been able to see easily

enough,

however, that Lucrece was anachronistically and

provocatively

set in a

Catholic arena of conscience, where “sin is clear’d with

absolution”

(Lucrece, 354; cf. EC, 114r:

“conscience is

cleared

by humble confession”), and yet where

the norm of absolute

perfection, which was sometimes urgently pressed upon the faithful in

the

teaching of the Counter-Reformation, might lead the radically devout to

a

martyr’s death. In this context such readers would be alerted by

Lucrece’s

description of herself as “martyr’d” (802) (even though she uses the

term

loosely, and she was not, Southwell pointed out, a martyr in the

Christian

sense) to the icons of martyrdom in which she appears after her death.

The

first suggests a rite of passage in a baptism of blood: [her

blood] doth

divide

(1737-39)In two slow rivers, that the crimson blood Circles her body in on every side... (cf. EC 141r: “martirdome is the ryver Jordan,” where Jesus was baptized; and 184r: “The redd sea of Martyrdome.”) The second

displays the power of the martyr’s sufferings and relics: They

did conclude to bear dead Lucrece thence,

To show her bleeding body thorough Rome, And so to publish Tarquin’s foul offense; Which being done with speedy diligence, The Romans plausibly did give consent To Tarquin’s everlasting banishment. (1850-55) (cf. EC,

149r : everye dropp of bloode, is able to doe as

much, and

somtymes

more forcible effectes, then the martyr himselfe, if he had remayned

alyve; 156v:

when [St James’] blood began to worke, the whole country yelded to his

dead

bones; 193r: It is a glory [for a martyr] to

shewe his

woundes.)

Catholics

deeply familiar with Southwell’s

writings might also have discovered martyrological parallels between

Lucrece’s

“will” which she promulgated before her death (1198-201) and the “will”

of

Christ, which Southwell

ascribes to the

dying redeemer “hanging upon the Crosse” (EC, 95v);[51]

or

between the “winged” flight of Lucrece’s soul

(1727-8) through

the “hole”

made in her flesh (1175) and the “winged” departure

of the

martyr’s soul

for heaven (EC, 144v-45r)

through the “holes

[made in their] bodyes” (EC, 194v). But the most

compelling moments of

Shakespeare’s poem for “papish” readers might have been those which

dramatize

the torments of conscience forced upon a woman who was perplexed in the

extreme

by the injunction to be perfect and the impossibility of being so: . . . no perfection is so absolute, That some impurity doth not pollute. (853-4) One of the

great sources of anguish for

Lucrece is her inability to quarantine the purity of her mind from what

she

believes to be the corruption of her body. At one point (as Shakespeare

follows

the story in Livy)[52]

she

attempts to do so: Though my gross blood be stain’d with this abuse, Immaculate and spotless is my mind; That was not forc’d, that never was inclin’d To accessary yieldings, but still pure Doth in her poison’d closet yet endure. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . May my pure mind with the foul act dispense . . . ? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . May any terms acquit me from this chance? The poison’d fountain clears itself again, And why not I from this compelled stain? (1655-9; 1704-8) And her family

and friends do not hesitate to reassure her:

. . . they all at once began to say,

Her body’s stain her mind untainted clears. (1710) But she finally

refuses to accept the consolation of their moral reasoning: “No, no,” quoth she, “no dame hereafter living By my excuse shall claim excuse’s giving.” (1714-15) It is an

elementary principle of modern

ethics that “intention” ultimately determines the character of an act,

and that

an upright will should save from blame a person forced to proceed

against her

own volition. Thus it is sometimes said that Lucrece’s thoughts

confuse, in a

way that is never resolved, the standards of a “shame culture,”

according to

which, ignorance or good intention may not prevent “pollution” by

outlawed

deeds, with those of a “guilt culture,” in which “sin” is committed

only and

entirely in an informed and consenting conscience.[53]

Speaking the language of both codes, Lucrece is indeed bewildered by

her

predicament. On the one hand she asserts that the rape has left her

mind

“Immaculate and unspotted” (1656), while her body has become a “temple

spotted,

spoil’d, corrupted” (1172). Her intention to resist the assailant thus

preserved her from guilt but not from shame rooted in physical

“spot”--a

disgrace which her husband might share with her (1065-72). On the

other, she

speaks as though her body, an indifferent thing, has been unaffected by

the

rape, while the spiritual treasure that resided in it has been rifled:

“Poor

helpless help, the treasure stol’n away, / To burn the guiltless casket

where

it lay” (1056-7). Her language of “shame” and “disgrace” has nothing to

do with

her conscience. Her language of “guilt” and “sin” has everything to do

with her

conscience, where, if anywhere, immorality must reside (750-56).

Finally,

Lucrece’s notion that her soul must “decay” after its “bark” has been

peeled

away (1169) seems only the anguished outcry of a mind too severely

wounded to

think clearly.[54] A modern reader, impatient

with this lack of

clarity, might say that Lucrece was violated, and then forced by custom

and

psychological reflex to believe in her guilt; she was stained truly in

neither

body nor mind. But Shakespeare insists on offering ideas in conflict

and even

in confusion. Was his main purpose to pursue these quandaries simply to

open up

without judging “a new interior world of shifting doubts, hesitations,

anxieties, anticipation, and griefs”?[55]

Or does the poem allow us to ask, with some hope of answers, such

questions as

these: to what extent did the poet make Lucrece a sympathetic

character? To

what extent a guilty one? To what extent a muddled victim? To what

extent a

martyr? Is the story of Lucrece more than a tale of tragic characters,

one

defeated by libidinous “Affection,” the other by a mind duped,

dismayed, and

excessively scrupulous? These difficulties ought to be considered in

light of

the crises of conscience faced by the Elizabethan Catholics to whom the

poem

seems at some level addressed. That a pure

heart could be insulated from

the guilt of a body compelled to an “external” crime was one of the

fundamental

tenets of “Nicodemism,” a casuistry used by Continental Protestants

(but

fiercely denounced by John Calvin) to justify their compliance with the

religious laws of Catholic monarchies.[56]

In Elizabethan England this casuistry was employed by many Catholics

who

believed that it relieved them of the necessity of becoming recusants.[57]

As

we have noted, such flexibility, though approved of by some Catholic

religious

teachers, was generally resisted by voices of clerical rigor, like that

of

Garnet. As early as 1567, Nicholas Sander denied solace to those who

believed

that a heart could be sovereign in its purity because distinct from its

body:

“it divideth one man in twain, setting the heart in one cumpanie, and

the bodie

in an other as though anie man could go to church except his hart

caried him

thither.”[58]

And

in 1593, the year before Lucrece was published,

Garnet insisted

with

some vehemence that those who brought their bodies to the churches of

heretics

could not by some mystical division leave their souls in the Catholic

Church.[59]

This is precisely the view advanced by Garnet’s colleague Robert

Southwell, who

in the Epistle of Comfort takes Calvin’s side

against the

“Nicodemites,”

arguing that “goinge to a churche of a contrary beliefe, is . . . To

part

stakes betweene God and the divell assygning the soule to one and the

body to

the other” (172v). English Catholics who

conformed to their

government’s laws concerning church attendance under threat of

punishment were

thus denied the saving expedient of believing that this forced external

compliance was trivial and that, in the words of Lucrece’s family, a

“mind

untainted” might clear a “body’s stain.” Like Lucrece,

the spiritual integrity of

these believers was assaulted by Tarquins who were in personal terms

their

“kinsmen” (fellow English Christians [cf. Lucrece,

237]) and in

political terms the “sovereign” state (cf. Lucrece,

632). Like

Lucrece,

they were both individuals and a corporate community--a “Troy” (1547:

“so my

Troy did perish”) liable to the deceitful incursions of the “Sinons”

(1541) of

the world (spies, informers--greedy and jealous friends among them, and

smiling

villains in high places).[60]

If

like Lucrece they yielded to rape without a struggle, it may have been

because

violent resistance seemed futile, and many could not believe the

rigorists who

found them guilty of a fundamental betrayal of their faith. But there

were

those, like Lucrece, whose consciences needed “perfect” purity and

could find

none in submission, even if it were passive and wholly external. Their

mental

agonies could be great, as may be seen in the case of one Francis

Wodehouse of

Norfolk, reported by the Jesuit William Weston:

“That proclamation of the

Queen,” he said, “did not touch me lightly. On the contrary, it lay

like a load

on my mind. It was not a matter merely for myself, not just a question

of

imprisonment. My wife, my children, my whole family and fortune were

concerned.

At a single blow all would be gone together. Yet, if I submitted, I

would have

to face perpetual disgrace in the eyes of decent men: and not that

only, but

infamy and the stigma of cowardice as well, and before God, the assured

and

inescapable jeopardy of my soul. And on top of it all,” he continued,

“came the

entreaties and prayers of my friends. . . . they exaggerated infinitely

the

importance of these passing possessions, and insisted how rash and

regrettable

it would be to refuse to purchase immunity from disaster by a single

visit to

church. Finally,” he said, “I was timid. I saw the best course, and

followed

the worst. . . . The feast day came when I had to be present.

Immediately I

entered the church . . . my bowels began to torture me. A fire seemed

to kindle

in them and in a few moments flared up. The torment was acute. The

flame rose

right into my chest and the region of my heart, so that I seemed to be

boiling

in some hellish furnace. . . . At last all my intestines seemed one

furnace of

fire.” Wodehouse left

at the end of the service,

trying to douse the fire with mugs of ale at a nearby tavern, but to no

effect.

Calmed by his wife and a priest, he eventually made his way to the

Anglican

bishop of the place, and told him he would never again comply with the

statute.

The bishop “clapped him into prison,” where he remained for four years.[61]

We

should note that Wodehouse shared Lucrece’s horror of “disgrace” and

“infamy”

as well as her detestation of sin. Like her, he felt coerced to yield

to

iniquitous force for his family’s sake (cf. Lucrece,

533). He

“submitted,” as she confusedly came to believe that she had done

(1035-6),

having listened to the mitigating words of friends before rather than

after

doing so. He suffered personal agonies for that submission, both in his

mind

and in the “criminal” body that failed to concur with it (Lucrece’s

blood

itself was “stained” by Tarquin [1743]); and, one infers, he atoned for

his sin

and saved his name by self-consciously making himself a martyr. Martyrdom for a

Catholic was salvific:

blood from martyrs’ wounds purified even more powerfully than the

waters of

baptism. Southwell wrote at some length on this point: “To the baptised

all his

sinns are forgeven. In the Martyr all his sinnes are quite

extinguished. . . .

Martirdome [doth] so clense the soule from all spot of former

corruption, that

it geveth ther-unto a most undefiled beautye. . . . it . . . clenseth

us both

from the myre and from the stayne and spot that remayneth after it. . .

.” (EC,

138v-39r). “Corruption,”

“mire,” “stain,” “spot”:

these

are words in which Lucrece reveals her obsession with the purity that

she

believes she has lost. And when she seeks to recover it, she does so in

blood:

“My blood shall wash the slander of my ill” (1207). At this point we

can

understand how a Protestant would have found her a “papish” heroine,

relying as

she does on her own “works,” her own “blood,” for absolution, instead

of

helplessly drowning herself in the Blood of the Lamb. Of course

Lucrece, in her

own age, knew no such savior; but Elizabethans both Catholic and

Protestant

would know the signs of a pagan “martyr” when they saw them. Another feature

of Lucrece that

would have been of interest to Catholic readers is the special and

somewhat

curious emphasis given in the poem to “treason” (in lines 361, 369,

770, 877,

909, 920). Although Lucrece is a private citizen and Tarquin the

prince, he is

accused more than once of this crime, which would usually be committed

against

rather than by him. Perhaps, as a commentator has noted, readers are

meant to

consider in this motif Tarquin’s “self-betrayal” as much as his

“treachery toward

Lucrece.”[62]

Or

perhaps his crime is treasonous in that it leads directly to the

downfall of

the monarchy. Even so, his assault on Lucrece herself is at least

metaphorically traitorous: . . .

his guilty hand pluck’d up the latch,

And with his knee the door he opens wide. The dove sleeps fast that this night-owl will catch; Thus treason works ere traitors be espied. (358-61) And English

Catholics, who were forever told by Elizabethan and Jacobean

governments that

they suffered not for religion but for treasonous acts against the

state, would

have appreciated the fine irony in this juridical characterization of a

prince’s assault on a private woman. Those who knew Southwell’s Epistle

of Comfort might also have recalled the

twist given by the

author to the

whole question of criminal rebellion. “If a subjecte,” he asks, “should

make a

lawe, that al the estates of the Realme should leave the obedience of

theyre

true Queene, and only submit them selves unto him: And shold prescribe

that in

token therof they all sholde come to his Pallace, and attende there,

whyle his

servantes did Pryncelye and regall homage unto him; were not the

obeying of

this lawe a consente to his rebellion? And the presence at his Pallace

a

sufficyente sygne of oure revolte from our Soveraygne?” Southwell then

declares

that this is “our very case.” “The Queene is the Catholicke Church. The

rebellious subjecte, resembleth the enemyes therof. The lawe

commaunding from

the Queenes, and forcing to her rebels obedience, the penall lawes

terrfyinge

us from the Catholycke relygion, and enforcing us to the heretycal

service. The

comminge to his Pallace whyle he is honoured as Kynge, is lyke the

comming to

Church while heresye is sett forthe, as true religion.” If, he

concludes, “this

point shold come to the scanning of any seculer tribunal, the leaste

faulte

that the offender could be condemned of, were highe treason”

(EC,

169v-170r,

emphasis added). In

the Epistle

as in Lucrece, it is the persecutor not the

persecuted who is

the truest

traitor. And in the Epistle as in Lucrece,

treachery

will lead to

“revenge”: Lucrece desires it (1180); her blood symbolically seeks it

(1763);

revolution achieves it. Southwell devoutly predicts it, writing a whole

chapter

of his work as “A Warninge to the Persecutours”: “The voyce of the

bloode of

youre murthered brethren cryeth out of the earth, against you. . . .

puttinge

Catholikes to deathe, you digge your owne graves. . . . by barbarouslye

martyring [your brethren, you] send them to heaven, there to be

continuall

soliciters with God for revenge against theyre murderers . . .” (EC,

197r,

199r-v). Vengeance had, of course, been part of

the original

Roman

“history”; but like so many other elements of that narrative, its

resonance

with contemporary conditions may have been among the reasons for

Shakespeare’s

choice of the story. Read from this perspective, Lucrece begins to yield answers to questions that have been posed about it from the beginning of this chapter. The anachronistic “fusion” of “Roman” and “Christian” standards of value does not show the author evasive or lacking control. On the contrary, his purpose was to demonstrate continuities between ancient and modern Rome in the religious ethic of the Counter-Reformation, as its moral imperatives affected the political life of the English nation and the personal lives of many of its citizens. The “confusion” of the heroine is not an aesthetic blemish, but emerges naturally in a plausible dramatization of psychological dilemmas comparable to those faced by “Romans” in late sixteenth-century England. It could never be within a poet’s competence to resolve them, though he might, as Shakespeare did, give them a sensitive portrayal and analysis. In doing so, he overcame the difficulty that modern criticism would find in making a “political” poem out of a narrative that dwells at great length not on overt political actions but on the “sufferings and predicament of the heroine.”[63] In Lucrece, politics cannot be separated from the individual tragedies that it begets. Since the poet is intensely interested in both the public and private significance of character, he gives to Tarquin (as no other writer before him saw need to do) a mind as well as a function. Tarquin is a prince, and his actions can never be entirely his own. With his fortunes a monarchy may fall, and it will. Yet if he is an emblem of state power, he is no faceless, unthinking one, but a villain with a conscience, whose actions are all the more reprehensible for their having been thought through. His lust for Lucrece’s body is hardly a negligible fact, and Shakespeare depicts the psychic “flames” with great vividness. But Tarquin’s sexual yearning is presented as somehow less important to him than his passion for “ownership.”[64] Lucrece is the “jewel” or “treasure” that an “owner” (her husband) should have protected from an intensely competitive “thief,” who strives to usurp “possession” (15-35, 305, 413). One way of viewing the lust for proprietorship is to consider it as a basic symptom of “patriarchal” passion. Another way is to see in it a symbol of the struggle between state and church for possession of the individual “subject,” body and soul. Since it is Tarquin, the prince, who is jealous of another’s “sov’reignty” (37), a dominion which implies limits to his own, and who “like a foul usurper went about / From his fair throne to heave the owner out” (412-13),[65] his claims, and therefore those of the state, are both nullified and shown to derive from perverse instincts. The libido dominandi is symptomatic of a grave moral and political pathology. One need not be a “Republican” to believe that tyrants like Tarquin and his father, to whom certain “noblemen of Rome” (including Collatine, Lucrece’s husband) gave allegiance in spite of their crimes (Argument 6-7), should suffer “everlasting banishment” (1855). But is there something perverse about Lucrece as well? Moralizing critics from St. Augustine to his twentieth-century epigones have asked with unpitying logic about her motives: “Si adulterata, cur laudata; si pudica, cur occisa?”[66] (“If adulterous, why is she praised; if chaste, why did she kill herself?”). The questions imply that she may be guilty either of bad faith (did she secretly “consent”?) or unholy desperation. Running counter to these suspicions, however, is a tradition at least as ancient that Lucrece acted heroically--that is, like the many Christian virgins of antiquity who killed themselves to preserve their chastity. Dante lodged her with the virtuous pagans. Chaucer called her a “seynt.” Some Renaissance painters depicted her as a dying Christian martyr, even as an imitator of the crucified Christ.[67] It is quite understandable that a figure who has inspired such contradictory responses through the ages would appear in Shakespeare (of all writers!) as a woman bound to defy conventional and straightforward assessment. Yet Shakespeare does provide grounds for judgments of her, even if he does not make them himself. We must wonder, of course, what the earl of Southampton thought of this “martyr’d” heroine. He had known martyrs, but he clearly chose, for whatever reasons, not to become one. It hardly seems possible that Shakespeare was presenting Lucrece to his patron as a model worthy of imitation. Neither is it likely that the poet would have portrayed for the earl as an object of derision a character whose struggles with her conscience mirrored in some sense those of his family and acquaintances (of his father, especially), and whose tragedy might be seen as too momentous for her to suffer the dry mock of a heartless irony. Southampton would surely see in Lucrece, as the narrator describes her, an “earthly saint” (85) of a kind unlike those who bore the title easily, lightly, and questionably in love poetry or complaint. Her sanctity is described in Christian terms--she dutifully bears the “yoke” of her “lord” (cf. Matt. 11:29-30; EC, 143v); but she is not preternaturally competent. Naive and provincial because unacquainted with evil (87), she receives a terrible initiation into a sordid world of duplicity and violence, “a wilderness where is no laws” (544). When asked by Tarquin to yield to his lust secretly and willingly, she utterly rejects his proposal, unable to accept that “A little harm” may be “done to a great good end” (528; cf. EC, 53r: “seeke not so greate a good by evill”). Lucrece argues with great resource against the rape, but confronted by the “uncontrolled tide” of Tarquin’s passion (645), she is finally as helpless as one would be who would take arms against a sea of troubles. She is forcibly silenced, and violated. We are told immediately that “she hath lost a dearer thing than life” (687). With this attitude she is already ripe for martyrdom, which in its epic or heroic form requires that one value a cause or principle more highly than personal existence. But though the narrator has compared her to a “virtuous monument” (391), she has not yet become one--is not yet like the statues of martyrs that Bernini would place, complete and unchanging in their perfection, atop the colonnade at the Piazza San Pietro. Though a victim, she feels in herself a “cureless crime” (772): she was “afear’d to scratch her wicked foe” and sensed within herself some kind of “yielding” (1035-6). Blame for this she first tries to ascribe to circumstances: to “Night” (772), to “Opportunity,” (876), and to “Time” (931). She would learn to “curse” (996). Her first thoughts of suicide (1044ff.) seem tinged with hysteria, for her grief is “wild” (1097), “mad,” (1106), without “law or limit” (1120). But a saint will not long resort to “excuses”; Lucrece stops coining them (1073). A martyr will not yield to hysterics. By fits and starts she controls her grief and will become “mistress” of her “fate” (1069). At one moment not sure that suicide is virtuous (1156-7), she resolves upon it anyway, as a means of purgation and recovery. Calmly she makes her final “bequests” (1181-1211). Having summoned her husband from the siege of Ardea, however, her passionate grief not yet spent, she finds “means to mourn some newer way” (1365). She surveys a painting of “Priam’s Troy,” like herself besieged, betrayed, and despoiled; a picture in which a part “Stood for the whole to be imagined” (1428). She sees in Hecuba an epitome of human ruin, and “shapes her sorrows to the beldame’s woes” (1458), reviving her frenzied complaints and her curses, blaming all, men and women, Paris, Helen, and Priam, whose uncontrolled lust and culpable weakness brought misery to thousands. The words are again wild, but not irrational. Like the besieged English recusant community, she wonders Why should the private pleasure of some one

Become the public plague of many moe? Let sin, alone committed, light alone Upon his head that hath transgressed so; Let guiltless souls be freed from guilty woe: For one’s offense why should so many fall, To plague a private sin in general? (1478-84) The point is in

Southwell’s writings, and in the thoughts of countless of the

faithfull,

whether inclined to martyrdom or not: it were a hard Course to reprove all Prophetts

for one Saul, all

Protestants

for one Wyatt, all Priests and Catholiks for one Ballard and Babington (HS, 16-7). As Lucrece’s

sorrow ebbs and flows, her husband, her father, and the

soldier-revolutionary

Lucius Junius Brutus arrive to receive her story, hear her call for

revenge,

and witness with dismay her self-murder, which is as ritualistically

decorous

as it could be. Collatine, her husband, and Lucretius, her father,

first react

to her death with helpless astonishment and vie with one another,

comically, in

their grief. Brutus drops the pretense of a madness he had assumed for

political reasons, scolds the others for their “childish humor” (1825)

and

scores the folly of Lucrece, who “mistook the matter so, / To slay

herself that

should have slain her foe” (1826-7). He brings the others into a league

to

pursue revenge, which is accomplished when Lucrece’s martyred body is

paraded

through Rome, an incitement to a rebellion that drives the Tarquins

from power. There is

condescension toward Lucrece as

the poem nears its end, not only from Brutus, but from the narrator. It

is the

latter who tries to elicit pity for the heroine by portraying her as a

“weak-made” woman (1260), like others of her sex with “waxen minds”

always

ready to be shaped by “marble”-minded men. Southwell had propounded

these

stereotypes, at times to show how saintly women could transcend

them--as so

many female saints of the Counter-Reformation did, in England as well

as on the

Continent.[68]

To

some extent Shakespeare’s poem demonstrates that transcendence, despite

the

misplaced sympathy of the narrator and the blind contempt of Brutus. In

the

narrative, we might ask, whose minds are in fact more “waxen” than

those of

Tarquin, Collatine, and Lucretius? Whose mind more “marble,” in her

state of

final resolve, than that of Lucrece? It is the mind of Lucrece that,

though

innocent and wayward, is the most deep and far-ranging. Her candor and

bravery

are grander than the calculated disguise of Brutus; and his unabashed

delight

at having a martyr’s relics to “use” in his political struggle does not

speak

well for his humanity or (since he lets the corpse take the lead in the

struggle for liberation) his fortitude. We may

conclude, then, that Shakespeare

created in Lucrece a heroine that his patron, a man of Catholic

upbringing and

Catholic sympathies, could admire. The theologians’ strictures against

suicide

have been deliberately confounded as Lucrece is brought to resemble

martyrs who

have surrendered their lives for principle, even if in this case the