|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

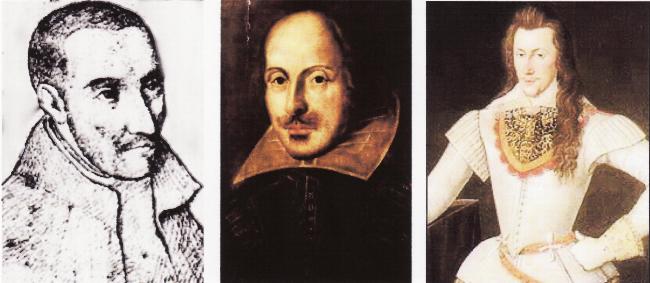

SHAKESPEARE, THE EARL AND THE JESUITJohn Klause |

|||||||||||||

|

CHAPTER

3

Ephesus, Rome,

and London

I On the evening

of December 28, 1594,

several months after the wedding of the Dowager countess of Southampton

to Sir

Thomas Heneage (on the second of May) and the entry of Lucrece

in the

Stationers’ Register (a week later), Shakespeare’s company performed a

version

of The Comedy of Errors at the Christmas Revels of

Gray’s Inn.[1]

It

has been suggested that the earl of Southampton sponsored the

performance,

seeing to the construction of the “Stage . . . and Scaffolds,”

arranging for

the admittance into the great hall of the “Company of base and common

Fellows”

who acted in the play, and paying them for their trouble.[2]

The association of Southampton with the Comedy at

this time (even though

it may have been written two or three years before its staging at

Gray’s)[3]

should lead us to inquire whether there were some special interest for

him in

the work, as in Venus and Adonis, in Lucrece,

and (depending on

the play’s date) as there were or would be in A Midsummer

Night’s Dream.

If Southampton had such an interest, did Shakespeare rely in some way

on Robert

Southwell’s writings, as he did in composing those poems and that play,

to

inspire it? Since, as it now appears, the author of Lucrece

had a

rationale for introducing Catholic elements into his Roman tragedy, the

Catholic overtones of the play he fashioned out of Roman comedy may

have served

just as deliberate a purpose. T. W. Baldwin,

who wrote more than any

other scholar of his day or ours about The Comedy of Errors,

discovered

what he judged to be two distinct attitudes toward Catholicism embodied

in the

play. Three years after completing an edition of the Comedy

in 1928,

Baldwin published a monograph, William Shakespeare Adapts a

Hanging, in

which he took great pains to demonstrate that the playwright had

witnessed in

1588 the execution of William Hartley, a Catholic priest hanged in

Finsbury

Fields not far from the Theatre, where Shakespeare may then have been

working.

Baldwin saw in Hartley and his plight inspiration for the character and

fortunes of the Comedy’s Egeon, the Syracusan

merchant nearly beheaded

for coming into Ephesus illegally, and felt that Shakespeare’s

sympathetic

portrayal of a figure modeled on a Catholic martyr testified to the

author’s

broad-mindedness. Certain that Shakespeare “retain[ed] the attitude of

the

government in its treatment of the religious struggle, of which Hartley

was a

victim,” Baldwin believed nevertheless that the playwright recognized

the

priest’s essential nobility and in the play “removed” his character

from the

religious to the commercial sphere to allow that virtue its due.[4]

If

Shakespeare could appreciate Catholic heroism, however, he seemed to

lack all

tolerance of Catholic superstition. Baldwin thought it probable, as he

later

wrote in another study of the Comedy, that Dr.

Pinch, the exorcist who

is ridiculed in the play, revealed his creator’s scornful attitude

towards the

Catholic exorcists who had created a great stir in England in the

1580’s--priests like the English Jesuit William Weston, made notorious

by

Samuel Harsnett in his Declaration of Egregious Popish

Impostures

(1603), a book of which Shakespeare would make liberal use in writing King

Lear.[5]

Since Baldwin’s contentions, occasionally noted but rarely taken

seriously, are

pertinent to our line of inquiry, their validity should be reviewed;

and

whatever truth they contain should be related to the evidence already

accumulated about Shakespeare’s connections with the world of Robert

Southwell. The passage in The

Comedy of Errors

that set Baldwin’s mind on a scene of execution or martyrdom is from

Act 5, in

which, after Antipholus of Syracuse and his servant Dromio seek asylum

in a

priory, and the Abbess keeps their pursuers from them, the Duke of

Ephesus is

about to pass before the abbey with his prisoner Egeon en route to the

captive’s decollation. An Ephesian merchant announces that

the Duke himself in person

Comes this way to the melancholy vale, The place of death and sorry execution, Behind the ditches of the abbey here. (119-22) Through a

meticulous comparison of the

topography of the scene presented by Shakespeare with that of the

locale of

Holywell Priory as it was in Shakespeare’s day (the abbey gate opening

onto a

street that led to a vale, where in October of 1588 two Catholic

priests were

executed; the vale lying behind the ditches of the abbey, and the

ditches

running on the side opposite the direction from which a procession to

the place

of execution would approach), Baldwin demonstrated that the playwright

had in

mind a particular London site with specific “melancholic” associations.

The

place would have been familiar to Shakespeare because not many yards

from the

Priory were the Shoreditch playhouses, the Theatre and the Curtain,

surely

known to him at this time. According to John Aubrey’s

seventeenth-century

information, Shakespeare once lived in Shoreditch. And whether or not

he

witnessed the executions that gave the vale an atmosphere of bloody

tragedy, he

might well have known of an event that the government had assigned to

the site

to advertise more widely than usual, in the wake of the Armada, its

legal

ruthlessness towards those who would deny its legitimacy as a spiritual

as well

as a temporal power. Baldwin thought

it likely that Shakespeare had

witnessed the event itself, considering that no other explanation could

account

for the resemblances between the circumstances and demeanor of William

Hartley,

one of the priests hanged in the vale (Finsbury Fields), and those of

the

play’s Egeon. The “hapless” merchant was a victim caught in the

international

animosities bred by a war of trade, which led both Syracusans and

Ephesians to

pass (in “solemn synods”) a law that prescribed death for any of the

one nation

who was found within the bounds of the other (1.1.11-19). This legal

situation

is partly analogous to the one faced by Catholic priests after 1585, in

which

year Parliament ruled that the very presence in England of a Catholic

subject

of the queen who had been ordained a priest beyond the seas after 1559

was in

itself treason, the crime subject to the usual capital penalties.[6]

That

Egeon was styled a “merchant” (indeed, at one point, a “reverent . . .

merchant” [5.1.124]) Baldwin found significant. For although a merchant

is

mentioned as the father of the twins in the Argument to Plautus’s Menaechmi,

the main source of The Comedy of Errors,

Egeon is a character

whom Shakespeare himself invented--with hints from the story of

Apollonius of

Tyre. Apollonius contained a storm at sea that

separated a husband from

his wife and child and transported the wife to Diana’s temple at

Ephesus, where

she became anachronistically (in Gower’s retelling of the tale) its

“Abbesse”

until her reunion with child and far-wandering husband.[7]

The procession of a “merchant” to a place of execution reminiscent of

Finsbury

Fields, haunted with the ghosts of slain priests, reminded Baldwin that

Jesuit

missionary martyrs like Edmund Campion and Robert Southwell had

represented

themselves as merchants. Southwell referred to himself as such in coded

correspondence with his Roman superiors (he speaks of a trader’s [i.e.,

Campion’s] having “load[ed] his vessel with English wares,” and having

“successfully returned to the desired port”; and he speaks of his own

“business” for the “firm”).[8]

Baldwin did not find “allegory” here, recognizing that “with allegory

we cannot

satisfactorily account for the [narrative] result.”[9]

Egeon represents, for example, neither a particular priest nor

priesthood; his

sons are not a pastor’s lost flock, his wife and her abbey not the

orthodox

national church which he thought had vanished but has miraculously

survived, in

the territory of a heterodox ruler, to save and give sanctuary to her

family.

The playwright’s imagination merely fused, opportunistically, elements

of

various literary sources with fresh historical memories to produce the

story of

Egeon, which suggested Shakespeare’s attitude to the events that

prompted it

without embodying a moral. Baldwin’s

extensively argued case for

seeing in the Comedy’s “melancholy vale” a

superimposed image of the

area around Holywell Priory is impressive and difficult to discredit.

His

proposal that a specific political execution associated with that site

inspired

the nearly tragic tale of the play’s Syracusan merchant is reasonable.

Without

good reason, however, Baldwin largely suppresses the religiously

derived

connotations of Egeon’s plight and leaves it remote from other elements

in a

play that, like Lucrece, is oddly rife with

religious allusion. Since The

Comedy of Errors is

conspicuously Plautine, we might expect it to have a pagan setting; and

indeed,

in the first scene Egeon blames his misfortune on the merciless “gods”

and the

Duke laments the hostility of “the fates” (1.1.98-9, 140). But

everywhere else the

vintage is modern, Christian, and specifically Catholic. History and

geography

are of the late sixteenth century; France’s wars of religion are

prominently

mentioned by characters who know modern European countries, America,

and the

Indies (3.2.95-138). Antipholus of Syracuse identifies himself as “a

Christian,”

and a merchant measures time by “Pentecost” (1.2.77; 4.1.1); we hear

biblical

references to Adam, Noah, and to the Prodigal Son, to “angels of

light,” Satan,

and other “devils” (3.2.106; 4.3.13-19, 49, 55-6, 71). Exorcism of evil

spirits

is attempted through prayers to “all the saints of heaven” (4.4.57).

From the

Catholic world of the play are Syracusan Dromio’s “beads” and sign of

the cross

(2.2.188); Adriana’s promise to “shrive” (offer absolution to) him for

his good

service (2.2.208); and of course the Abbess and her priory (5.1). More

important than these local religious references, however, is the play’s

general

tide of allusion to the history and writing of St. Paul, in particular

to episodes

in the Acts of the Apostles and to passages in Paul’s Epistle to the

Ephesians. Scholars have

noted a number of verses in

the nineteenth chapter of Acts that Shakespeare seems to have had in

mind as he

composed his comedy. It is there recorded that “Paul when hee passed

thorow the

upper coasts, came to Ephesus” spending “two yeeres” preaching to “all

. . .

which dwelt in Asia . . . , both Jewes and Grecians” (1, 10). Egeon

having

spent “Five summers . . . in farthest Greece [and] Roam[ed] clean

through the

bounds of Asia . . . , coasting homeward, came to Ephesus” (1.1.134).

Paul’s

Ephesus was the home of “certaine . . . vagabond Jewes, exorcists,” who

undertook to expell “evill spirits” from the possessed by invoking the

name of

Jesus, and who, because they lacked divine authority for their work,

were

themselves attacked by the demons and “wounded” (13, 16). The Ephesus

of Duke

Solinus also has a professional, inauthentic exorcist, Dr. Pinch, a

“conjurer”

(4.4.47), who invokes “the saints in heaven” in vain to drive “Sathan”

out of

the Ephesian Antipholus, and for his troubles is “bound,” has his beard

singed

then quenched with “puddled mire,” and is “with scissors nick[ed] like

a fool”

(5.1.170-75). Paul’s preaching brought him into conflict with devotees

of

Diana, whose celebrated “temple” stood in Ephesus (24-30). Reading of

this

temple probably reminded Shakespeare of Gower’s Ephesian abbey, with

its

abbess, thus inspiring the Comedy’s story of

shipwreck and separation

that ends in the priory of the Abbess Aemilia. From the

Epistle to the Ephesians, Paul’s

words about casting off “the olde man . . . , [to] put on the newe man”

(4:22)

lie behind the play’s “Old Adam new apparell’d” (4.3.13-14); and the

apostle’s

famous exhortation to his church, “Take unto you the whole armour of

God . . .

, having on the brestplate of righteousnes . . . , the shield of faith”

(6:13-16), is Syracusan Dromio’s precedent for self-congratulation: “if

my

breast had not been made of faith, and my heart of steel, / She had

transform’d

me” (3.2.145-6). When

Luciana declares

to her sister that men “Are masters to their females, and their lords”

(2.1.20,

24), she echoes the apostle’s injunction, “Wives, submit yourselves to

your

husbands, as unto the Lord. For the husband is the wives heade”

(5:22-3).

Adriana’s sense of oneness with her husband (the two are “undividable

incorporate” [2.2.122]) derives from a common New Testament axiom,

which is

repeated in Ephesians: “a man [shall] leave father and mother, and

shall cleave

to his wife, and they twaine shalbe one flesh” (5:31). The quarrels in

the Comedy

between masters and servants have a Pauline relevance: “Servants, be

obedient

unto them that are your masters. . . . And ye masters doe the same

things unto

them, putting away threatning” (6:5, 9; cf. Errors

2.2.20-49;

4.4.15-39). The association

of Paul and his Ephesus

with the events and characters of the Comedy is, we

may believe,

something much more than the playwright’s attempt (in accordance with

his

diminishment of the Plautine courtesan’s role in the story, and his

introduction into the plot of an idealistic romantic element) to infuse

a pagan

work with Christian piety. The parallels between Paul and Egeon, the

English

makeover of Ephesus--with its priory, its taverns (Phoenix, Porpentine,

and

Centaur), its penal laws, and its up-to-date, schoolmasterly exorcism

(to be

considered in detail later)--may have had an ideological purpose which

Baldwin’s research and analyses have misconstrued. Baldwin was

quite definite that Shakespeare’s

portrait of Egeon owed much to biblical writings about and by Paul, and

to a

great extent he was correct. In The Compositional Genetics of

The Comedy

of Errors, he carelessly claimed that “the

wanderings of Aegeon . . .

were transformed into terms of Paul’s missionary journeys”: it is

simply not

true, for example, that Paul “passed through Syracuse from Ephesus on

his way

to Rome,” for Ephesus was not a stop on his fourth and last sea voyage.[10]

Yet

Syracuse, Ephesus, and Corinth were all cities important at different

stages in

the life of the apostle, and these are the cities which figure

dramatically in

the Comedy’s first scene, as Egeon recounts his

journey “in farthest

Greece . . . , through the bounds of Asia,” “carried towards Corinth,”

and

coming to “Ephesus” (1.1.132-4, 83). The description of Egeon’s

shipwreck,

while indebted to the Aeneid, is, as Baldwin

claimed, at least as

reliant on the account of Paul’s shipwreck in Acts 27.[11] Since Baldwin

recognized the affinity

between Paul and Egeon as travelers and as victims of shipwreck, it is

strange

that he failed to see further resemblances, and implications, to which

his own

interpretation of the Comedy might have pointed. If

Egeon the merchant

is in some sense a literary avatar of Hartley the missionary priest,

both men

may be seen as anti-types of the missionary Paul. Egeon was imprisoned

in

Ephesus, Hartley in Ephesus/London; Paul wrote to the Ephesians from

prison--as

“an ambassador in bonds” (6:20).[12]

Egeon was condemned to be beheaded; Hartley was hanged, but generally

“treasonous” English priests were decapitated after being hanged

according to

the law’s letter; and according to tradition, beheading was the fate of

the

apostle Paul. A consistent allegorical link between Egeon and Paul can

go nowhere.

The imperfect analogy, however, between the martyred English missionary

and the

martyred missionary apostle is hinted at in the play’s actions and

allusions in

ways that might encourage Catholics to see the likenesses between these

two

historical figures, neither of whom appears in the comedy. The

similarities may

have political implications of great moment. As we have

noted, Baldwin thought that

Shakespeare’s admiration and pity for Hartley were more than offset by

the

playwright’s certainty that the English government’s handling of the

Catholic

question was appropriate. Baldwin found that Duke Solinus spoke

Shakespeare’s

own mind when he told the condemned merchant: “we may pity, though not

pardon

thee . . . ,” for to “disannul” the laws would be against a prince’s

“oath,”

and “dignity” (1.1.97, 142-4). The scholar believed it “notorious that

Shakespeare’s attitudes on political matters [were] always those of a

patriotic, almost an ultra-patriotic Englishman”; and he considered

that the

playwright’s external conformity to the prescriptions of the Protestant

state-church revealed his sincere conviction that the Catholic

“martyrs” who

died in defiance of the Queen’s “supreme” authority in spiritual

matters were

justly punished.[13]

But

whatever the evidence for Shakespeare’s chauvinism, his acquiescence to

the

state’s ecclesiastical laws proves little about the state of his

conscience in

an age of conflicting casuistries that allowed varying degrees of

conscientious

dissimulation, in circumstances that often forced individuals beyond

casuistry

into a reliance on private judgment when no other recourse seemed

adequate. As

proof of Shakespeare’s convinced adherence to the English church

Baldwin

offered his standing as godfather to William Walker in 1608, at which

he would

have been required to, and apparently did take Protestant communion.[14]

Baldwin was unaware that Hamnet and Judith Sadler, who gave their names

to

Shakespeare’s twins and were probably their godparents, later appeared

on a

list of recusants, prompting a recent historian to ask, “had

Shakespeare in

1585 knowingly chosen crypto-Catholics for his twins’ godparents, or

did this

pair convert later?”[15]

Conversion may or may not have come later; in any case it is

conceivable that a

godparent with Catholic sympathies might participate in a religious

ceremony

without the slightest hint of the religious conviction that the ritual

was

supposed to identify. Indeed many “Church papists” had their children

baptized

in Protestant churches, because the Roman church recognized the

validity of

such baptisms, and because “the taint of illegitimacy blighted infants

whose

baptisms were not officially registered.”[16] It is best,

then, not to read The Comedy

of Errors in light of a set of the author’s “assumed” beliefs

that the play

might seem to contradict. We should not take for granted that he

approved of

the law condemning to death a merchant (or a priest) for his mere

presence on

Ephesian (or English) soil. We should consider it possible that the

associations obliquely made through the play of a missionary priest

with the

archetypal Christian missionary were meant as a compliment to the

former and to

his mission, not just as a sign of sympathy for a noble man in his

suffering.

And we may examine the other Catholic elements of the play with an open

mind. One of these

elements is exorcism. As has

been mentioned, Baldwin’s survey of various episodes of this ritual in

England

of the late 1580’s led him to conclude that the Comedy’s

unfortunate Dr.

Pinch (transformed from the Menaechmi’s medicus

into an

exorcising schoolmaster) represented the Catholic priests whose folly

and

supposed wickedness Harsnett would expose at the beginning of the next

century.

The play does not, in fact, well accommodate such an interpretation.

The art of

dispossession was hardly a Catholic monopoly in late sixteenth-century

England.

Some Protestants showed themselves susceptible to its mysteries, even

the

martyrologist John Foxe, who expelled the devil from a student of law

in 1574.[17]

The

most notable of the Puritan exorcists was John Darrell, who began his

career as

an unordained preacher and assumed his struggles with the foul fiend in

1586,

when he treated a

young Derbyshire woman

(without complete success) and wrote an account of the incident for

Puritan

readership. Darrell resumed his exorcising career in the 1590’s, when

his

notoriety brought him into conflict with the authorities and subjected

him to

the scornful pen of Harsnett in A Discovery of the Fraudulent

Practises of

One John Darrell (1599). He gained a regular ministerial

position in 1598.[18]

It

has been speculated that Shakespeare had Darrell in mind when in Twelfth

Night, the Clown, wishing that he were “the first to have

dissembled in

such a gown,” assumes the Genevan black clerical costume before

approaching the

imprisoned Malvolio, whom he accuses of being afflicted by the

“hyperbolical

fiend” (4.2.1-6, 25).[19]

If

Dr. Pinch, a lay schoolmaster, may be said to resemble anyone (his name

is

tantalizingly close to that of R. Phinch, a Protestant assailant of

Catholic

“conjurations” in his book of 1590, The Knowledge or

Appearance of the

Church),[20]

it

is such a lay conjurer as Darrell was at the beginning of his career,

not a

Catholic priest.[21]

We

may recall that the nineteenth chapter of Acts, which helped to inspire

Shakespeare’s introduction of exorcism into the Comedy,

distinguishes

between genuine and bogus exorcists, between Paul and the Jews of

Ephesus who

adjured devils by “Jesus, whom Paul preacheth” (13). Lay usurpers of

clerical

authority, “freelancers” like Pinch and Darrell, resemble the vagabond

exorcists, their actions not necessarily an embarrassment to a church.

Indeed,

it is the Catholic abbess and her “order” that offer a sane, salutary

alternative to the foolishness of Pinch’s conjurations. “Be patient,”

the

abbess tells Adriana. Unaware of the “errors” that have driven

Adriana’s

husband to distraction, she determines by shrewd questioning that

Antipholus

(the one she is told about) is probably not possessed. She sees at

least the

partial truth that he has been “scar’d . . . from the use of his wits”

by the

“jealous fits” of his wife (5.1.85-86), and grants the man whom she

believes to

be angry and bewildered (his brother in fact) sanctuary in the priory: I will not let him stir Till I have us’d the approved means I have, With wholesome syrups, drugs, and holy prayers, To make of him a formal man again: It is a branch and parcel of my oath, A charitable duty of my order. . . . (5.1.102-7) That

Shakespeare placed charity and stern

common sense so conspicuously in the abbey suggests that, if he were

aware when

writing the Comedy of the bizarrerie

of Catholic exorcisms in the

1580’s, he did not consider these isolated instances a defining mark of

institutionalized superstition and deviousness in the church. Perhaps

he knew

of the official policy of the English mission that “In these times

exorcism is

not to be practised except very cautiously, prudently, and rarely,

because it

does not always have effect, for not even the Apostles themselves could

cast

out all devils” (cf. Matt. 17:16-21; Luke 9:39-43).[22]

He was certainly aware that Southwell did not find thrilling the power

of the

exorcist. “We never read,” Southwell said in his Epistle of

Comfort,

that the Apostles “rejoyced at their power over devils . . . , which

well

declareth how muche they prised theire persecution, more than their

authoritye.

And therefore Christ sayde Beati estis not for commaunding devils. . .

: But

beati estis cum maledixerunt vobis homines, & persecuti vos

fuerint . . .

propter me. You are blessed when men hate you, and persecute you . . .

for my

sake” (105r). Southwell, although he believed in

diabolic possession

and that “Gods Saints [were given] greate authoritye” over devils (EC,

69v,

165r, 178r), was himself

an Egeon, not a Pinch.

Shakespeare would read years later Harsnett’s mockery of credulous

supernaturalism and cruel authoritarianism in the priests and

“demoniacs” of

Dedham and elsewhere; and he would register his reactions in King

Lear;[23]

but

in the early 1590’s his Comedy of Errors was rather

kind in its

allusions to priest and church. Perhaps his own inclination made it so;

perhaps

Southampton found this kindness, as well as the play’s hard comic

brilliance,

attractive for presentation at Gray’s Inn. In a government

survey of the state of

religious conformity at the Inns of Court in the late 1570’s, Gray’s

and the

Inner Temple had the highest percentage of “known and suspected

catholics.”

Through the eighties, Gray’s, which was strongly represented in its

membership

by men from Catholic Ireland, Lancashire, and other northern locales,

continued

to show up in reports as hospitable to popery, a place where priests

were

thought to have been sheltered and where masses were said. It was from

Gray’s Inn,

where he had converted several fellow members, that Henry Walpole, an

admirer

of Edmund Campion, left to join the Jesuits (in 1584), then to become a

fellow

prisoner in the Tower with Robert Southwell, and an executed “traitor”

not long

after Southwell’s death.[24]

Swithin Wells, a schoolmaster with longstanding connections with the

Southampton family, had a house in Gray’s Inn Fields (an area noted for

its

“conferences” of “seminaries & Catholics”), where the

pursuivant Topcliffe

arrested a company at mass, and outside of which Wells and the priest

Edward

Gennings were hanged in 1591.[25]

Some of the Inn’s members who would view The Comedy of Errors

three

years later, including the earl of Southampton himself, may have

witnessed the

bloody event. Even in 1594, as Southampton must have known, a play like

the Comedy

at Gray’s would likely speak to some in the audience who were, as the

saying

went, “popishly affected.” Did Southwell

help it speak? Given what we

have learned thus far about Shakespeare’s reading, it would seem

strange if the

Jesuit had not done so. Southwell wrote bitterly about the “Statute”

that

prefigured the law in Ephesus that almost cost Egeon his life: “we

[are]

allwayes arraigned and Cast upon the Statute of Coming in England. . .

. To avouch

us Traytors for coming into England or remayning here, is an Iniury

without

ground . . .” (HS, 30). Blessing Paul’s missionary

“cheynes,” he

mentioned the shipwreck in Acts 27, which, as Baldwin has shown, had

features

in common with Egeon’s (EC, 105v).

And Southwell’s writings

are much echoed in the exchange between the Duke and Egeon in the

play’s first

scene, the Jesuit’s voice mingling with others (of Plautus, Virgil, the

author

of Acts, and John Gower) that have contributed to the total effect. In poetry and

in prose, Southwell is

forever making use of metaphorical “tempests” of one kind or another.

In his Epistle

of Comfort, addressing “the reverend priestes” who like the

“reverent

merchant” Egeon were under sentence of death, he exhorts them to

courage by

declaring that the troubled sea of the world is well left behind for

the “safe

porte” of eternity. From this part of his Epistle

and its surrounding

contexts, with its figurative storms and literal stress (centered on

fols. 112r-117v),

we can find much of the language and imagery that appears at the

opening of the Comedy. We have already seen

Shakespeare’s

recollection of these same

pages in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, when Titania

describes her pregnant

votaress gazing on the beach at the “traders on the flood.”[26]

In the Comedy, Egeon draws from Southwell’s

material in narrating the

loss of his wife, son, and servant in a shipwreck.

Errors

1.1.48-119

Epistle

of Comfort

[She] soon, and safe, arrived where I

was.

115r:

quicklye landed in a safe

porte

.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . in the self-same inn, 112r-v: the travayler[s] Inne . . . the marchant . . . A mean woman was delivered woman great with childe . . . Of such a burthen . . . . the tyme of her . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Yet the incessant weepings of my wife, 113r-114v: alwayes . . . weepe. . . wife; . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . And piteous plainings of the pretty babes, 117v: [man] beginneth his course with pitifull . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . [We] Fast’ned ourselves at either end 102r: fastened; 107v: ende; 96v: mast the mast, And floating straight, obedient to the stream, 117r: the streame kepeth on an unflexible Was carried towards Corinth course; 116r: caried; 132r; Cor[inthians] 114v-115r: attayne dyverse shores . . . by healpe of a selye plancke . . . , by some fragment of the broaken shippe At length the sun, gazing upon the earth, 116r-v: earth . . . sunne; Dispers’d those vapours that 116v: vapoure that soone vanisheth; 106v: offended us; offenders And by the benefit of his wished light 115v: benefitt; 121v: wished; 120v: lighte; The seas wax'd calm . . . . 115v: altered their stormes into a calme wind . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . We were encount’red by a mighty rock, 117v: with divers encounters; 115v: mightye . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114v: beaten with the billowes against the stonye rockes And therefore homeward did they bend their 117r: home . . . keepeth on . . . course; course. Thus have you heard me sever’d from 120r: severeth from the worlde . . . , their my bliss, Parradise That by misfortunes was my life 128r: misfortune; 136v: lamente that our prolong’d inhabitance [i.e., life] is prolonged Of special note

is Southwell’s picture of shipwrecked passengers saved by fragments of

their

vessel. In Plautus’s Menaechmi, the twins are

separated by kidnapping;

and in Gower’s Confessio Amantis, Apollonius’ wife,

presumed dead, is

sent away from a ship in a chest that floats to Ephesus.[27]

Shakespeare here preferred Southwell to his other sources. The Comedy of

Errors opens with the entrance of the Duke,

Egeon, a Jailer, Officers (assumed by editors to be present),[28]

and

other Attendants. Within the space of a few pages, Southwell had spoken

of

“Dukes” (116r), an “Officer” (121v),

a “Jayler” (128r),

and “Gedeon” (134r), perhaps unwittingly

suggesting to the

playwright how to populate his opening scene. Commentators have usually

considered that Shakespeare derived the name “Egeon” from the Aegean

Sea which

the merchant had relentlessly traversed in search of his sons.[29]

A

less simple possibility--though a quite plausible one if Baldwin’s

thesis about

the missionary behind the merchant is true, and in view of what can

otherwise

be shown about the reliance of the Comedy on

Southwell--is that “Egeon”

is derived anagrammatically (“E[d]geon”) from “Gedeon” (that is,

Gideon; cf.

“Caliban” and “cannibal”). In the Epistle of Comfort

this Judge of

Israel is presented as a model for the church’s missionary “Captaynes”

(98r,

134v), ready to suffer heroically to overcome

the false religion of

Baal.[30]

Such a derivation would be appropriate to the conceptual seriousness of

Egeon’s

story (he would hardly be “Thamesian” or “Atlanticus” were his watery

venue

different), placing him in a category different from that of characters

whose

names immediately announce their comic flatness (“Pinch,” or “Dromio”

[“Runner”

or “Messenger”]). And it would of course strengthen the case for the

drama’s

religious subtext. Other names conceivably suggested by Southwell’s

works

appear in the play: the Epistle of Comfort has

“Angell” and “angelus”

in proximity with a goldsmith (76v, 82r)

(cf. “Angelo, a

goldsmith,” a character of Shakespeare’s invention).[31]

An Epistle unto his Father (a work with other

connections to the Comedy)

has, along with a “goldsmith,” a “Baltazar” and a “merchant” (6, 7, 12)

(cf.

“Balthazar, a merchant”). Names, of course, are much less important

than

situation and action; but Shakespeare does seem on more than one

occasion

(especially in Titus and Measure for

Measure, it will be seen) to

have had help with nomenclature from Southwell. The Comedy’s

first scene has in it

nothing at all of the comic. It introduces us to a condition of

commercial

warfare so bitter that each Prince of the rival powers, Syracuse and

Ephesus,

will put to death anyone found in his city who was born in the other’s.

Ephesian merchants have already been killed in Syracuse (1.1.7-9). In

Ephesus,

the merchant Egeon is about to lose his life, guilty of nothing more

than his

provenance. The Duke of Ephesus expresses regret that a man of such

hapless

dignity as Egeon must endure the full rigor of a law that, in the

absence of a

huge ransom, requires his death; but princely majesty would be wounded

by a

pardon, and, it is implied, wars are not won through weakness. These

fictions

are based on no source, unless the source be history itself, in which

case they

allude to the religious conflicts that divided Catholic and Protestant

Europe in

the sixteenth century. Indeed, Shakespeare refers later in the play to

the

French wars of religion, when “France” is described as “arm’d and

reverted,

making war against her heir” (3.2.123-4), thus alluding to the Catholic

League’s struggle against the Protestant Henry of Navarre, whom Henry

III had

designated his successor in 1589. Passionate politics in Syracuse and

Ephesus

may remind one of religious strife within England itself. Curiously,

Duke

Solinus speaks of the “jars” between his city and Syracuse as

“intestine,” and

of the Syracusans as “seditious” (1.1.11-12), as though the wars were

internecine--that is, as in the reign of Mary Tudor, when English

Protestant

“heretics” were executed and large numbers went into exile as unwelcome

on

their native soil; as in the equally bloody (though more protracted)

tenure of

Elizabeth, when laws alienated Catholics remaining in England and, as

in the

play, prescribed the slaughter of merchant-priests who dared to set

foot there. Southwell, the

self-styled “merchant,”

would fall victim to the later regime’s “Statutes,” against which he

protested

not only in the Humble Supplication, but

inferentially in the Epistle

unto his Father (written in 1588 or ’89): in particular, he

would be

condemned according to the law of 1585 that made it treason for any of

Elizabeth’s subjects who had been ordained “beyond the seas” after the

Act of

Uniformity 1559 to be in England without taking the Oath of Supremacy.[32]

In

the Epistle he introduces a premise that provides

some basis for the

tale of Egeon. This story is always seen as arising out of the saga of

Apollonius of Tyre (upon which Pericles would later

depend); but it

needs a supplement. Apollonius, like Egeon, is separated from his wife

and

child at sea and after many years is reunited with both, the wife

having become

“Abbesse” in the Temple of Diana at Ephesus. But in Apollonius

there is

no war of merchants (Apollonius himself is a prince), no bloody laws to

threaten them, no years of searching for a lost family (for the Prince

believes

his wife, and later his daughter, to be dead). Southwell, on the other

hand, is

a son, acting also on behalf of his siblings (EF,

19), who desperately

seeks his father, to redeem him from the sin of schism and his soul’s

death.

The “engraffed laws” of the missionary’s country, however, which he has

violated at risk to his own life, force him to live “like a foreigner”

in his

own land (EF, 3-4). In his mind family roles are

fluid, for he is not

only a son to his parent, but a spiritual “father”--indeed, a “brother”

as well

(EF, 6-7). He thus combines in himself the offices

of both of the Comedy’s

seekers: father outlawed and condemned in search of his son, brother in

search

of brother. His imagination is filled with the threat of “storms,” with

dangerous

sea voyages, ships that threaten to be “dash[ed] . . . upon the rocks,”

safe

ports and harbors (EF, 9, 18), and a voyage filled

with “error” that

ends in a holy “sanctuary” in the “city of refuge” (EF,

18). That

sanctuary is the Catholic Church, which is “a fold and family” (EF,

12),

or, like the Comedy’s abbess in her priory, a

“mother” (EF, 18).

Aemilia, both nun and nurse, would heal, she says, “with the approved

means I

have, / With wholsome syrups, drugs,

and holy prayers,”

performing the “charitable duty of my order”

(5.1.103-7)--much as

Southwell the priest tells his father that he would bring him, out of

the “duty

of piety” and the fire of “charity” (EF,

4), “spiritual substance

to enrich you . . . , medicinable receipts against your ghostly

maladies . . .

that my drugs may cure you, my prey delight you”

(5) (cf. EC, 21v:

“Where God purposeth to heale . . . , he ministreth bitter sirroppes”).

By Aemilia’s estimate,[33]

she

has gone “Thirty-three years . . . in travail / Of . . . my sons

(5.1.401-2),

like the “three and thirty years in pain” that Christ, says Southwell,

wandered

“for the behoof of our souls” (16).[34] The political

and religious motifs at the Comedy’s

beginning and end may be said, then, to have been evoked by Southwell.

Between

these points there are further signs of his influence. In act 2, scene

2, for

example, when Adriana believes that her husband has taken “Some other

mistress,” she muses nostalgically on a more romantic time: The time was once, when thou unurg’d wouldst vow That never words were music to thine ear, That never object pleasing in thine eye, That never touch well welcome to thy hand, That never meat sweet-savor’d in thy taste, Unless I spake, or look’d, or touch’d, or carv’d to thee. (113-18) Her words are

reminiscent of Southwell’s description of the captive judgment of a

young

knight in love with his lady: The colours that like her seme

fayrest, the meate that

fitteth her taste sweetest, the fashion

agreable to her fancie

comlyest . . ., her sayinges oracles. . . .

whatsoever pleaseth her,

beit never so unpleasante semeth good, & whatsoever cometh from

her beit

never so deare bought and of little valew, is deemed pretious. . . (EC

34v).[35]

Adriana’s

husband

eventually bridles at his wife’s accusations, threatening her: with these nails I’ll pluck out these false eyes That would behold in me this shameful sport. (4.4.104-5) Southwell had

reported the sufferings of the Roman Regulus, stuck full of “nayles”

to save his honor, and of

Hasdrubal’s wife, who at the conquest of Carthage “rather chose to

burne out

her eyes . . . then to beholde her

husbandes miserye” (EC,

126v).[36] The play’s

comic foolery also owes

something to Southwell’s texts, most notably when Dromio of Syracuse

offers

some of the more dense and cryptic banter in the Comedy,

asking his

master if he had seen the arresting officer: Master, here’s the gold you sent me for. What,

have you got the picture

of old Adam new-apparell’d?

S. Ant. What gold is this? What Adam dost thou mean? S. Drom. Not that Adam that kept the Paradise, but that Adam that keeps the prison; he that goes in the calve’s-skin that was kill’d for the Prodigal; he that came behind you, sir, like an evil angel, and bid you forsake your liberty.[37] (4.3.12-21) The references

are biblical, of course, but they appear in a patchwork of texts from

Southwell. In Marie Magadalens Funeral Teares, in a

disquisition on

Adam’s fortunes in Genesis, the interlocutor reflects on the symbolic

significance of post-Edenic clothing: When Adam had sinned in the

garden of pleasure, hee was

there apparelled in dead beastes skinnes, that his

garment might betoken

his grave . . . (46v).

That Adam so

“apparelled” is also associated with a “prison” is explained by

Southwell’s

observation, on the previous page, that “Adam was . . . taken captive

by the

divell [just as] in a Garden Christ was taken prisoner”

(46r). “Keepers

of prisons”

are mentioned in The Epistle

of Comfort on 92v, “Pardayse”

on 95v, “Adames

garment of dead beasts skinnes” (again) on 118v,

the “divell”

(cf. “evil angel”) on the same page, an arresting

“officer” on 121v,

“sheepes skinnes” and “gotes skinnes”

on 126r, “libertye”

and “the

prodigall Sonne” on 133v.

All of the materials of Dromio’s imaginative conceit thus come from two

parts

of Southwell’s cabinet, combined exotically by the playwright’s

imagination. Southwell is

“in” The Comedy of Errors,

then, alongside St. Paul, hidden behind Plautus, Gower, Gascoigne,

Lyly, and

others, and party to what has usually been considered a “farce”: either

farce

pure, simple, and weightless,[38]

or

a “weird,” imperfect fusion of different literary forms, like “farce

and

romance,”[39]

that only recently has been interpreted with an attitude of high

seriousness.

For some commentators, “there is [in the play] nothing really to think

about--except, if one wishes, the tremendously puzzling question of

what so

grips and amuses an audience during a play with so little thought in

it.”[40]

At

the other extreme, a critic has claimed for it the status of “a signal

text of

early modern culture.”[41]

Surely there must be a less drastic approach to judging the play that

is more

true to its modest excellences than either dismissal or sublimation. That

the Comedy contains “serious” elements is

undeniable. But they may be of

no greater moment than its absurd coincidences, slapstick aggressions,

and

antic word play which as provocations to laughter need no higher

justification.

Farce may contain grave issues without allowing them gravity. It can be

powerful enough to enfeeble and make of no account even the “tragic”

actions

that it enfolds--as when in the film Easy Street

Charlie Chaplin gasses

a nemesis by forcing his head into a street lamp.[42]

The indifference of farce to meaning may seem like licensed escapism:

“Melodrama and farce are both arts of escape,” claims Eric Bentley in a

classic

essay, “and what they are running away from is not only social problems

but all

other forms of moral responsibility.”[43] Or it may point to

interpretive and

psychological principles of a different order. “Like dreams,” says the

psychoanalytical critic, farce may couple “a functional denial of

significance

with often disturbing and highly significant meaning.” To the

postmodernist

this may be a solemn truth, subverting meaning, revealing “the

impossibility of

discovering any single core of fantasy that ‘governs’ a text.”[44]

More historically-minded readers, however, will wonder if Shakespeare

wrote The

Comedy of Errors as the kind of farce that in the purity of

its modern or

postmodern definitions would be free from various kinds of

“responsibility” or

in thrall to the pyrrhonic compulsion to undermine coherence and

certainty. In contrast to

the breezy amorality and

comic callousness of Plautus’s Menaechmi,

Shakespeare’s play seems steeped

in pieties that refuse to let the recklessness of farce have its way.

Egeon’s

recounting of his losses may belong in a fairy tale, but unlike the

death of

the Syracusan merchant mentioned perfunctorily in the Roman play’s

Prologue,

the threat to his life, with its contemporary political resonance,

seems both

real and calculated to create a pathos that cannot be entirely

forgotten or

laughed away. There is no love in Plautus’s Epidamnum, no serious

reflection on

the mysteries of personal identity and marital union. Menaechmus the

“Citizen”

finds his wife a mere nuisance and does not object when at the end of

the play

his servant proposes to auction her off with his slaves and other

chattels.

Shakespeare’s Antipholus and his wife, transported to an Ephesus rich

in

biblical history, have a troubled marriage, but the solutions to their

difficulties are prescribed in the Pauline teaching on hierarchy and

reciprocity, and on the mystical union of two in one.[45]

Lines such as the following do not have the flavor of farcical

impertinence: How comes it now, my husband, O, how comes it, That thou art then estranged from thyself? Thyself I call it, being strange to me, That, undividable, incorporate, Am better than thy dear self’s better part. Ah, do not tear away thyself from me; For know, my love, as easy mayst thou fall A drop of water in the breaking gulf, And take unmingled thence that drop again, Without addition or diminishing, As take from me thyself and not me too. (2.2.119-29) The Dromios are

beaten by their masters, as in a farce, but the violence is not free

from St.

Paul’s moral strictures sent to the masters of Ephesus: “Servants, be

obedient

unto them that are your masters. . . . And yee masters doe the same

things unto

them, putting away threatening . . .” (Ephes. 6:5-9). Even the

buffeting and

burning of Dr. Pinch, farcically irresponsible as it is, derives from

the

“wounding” of the false exorcists in Acts 19, and therefore is not

wholly

without moral significance. If The

Comedy of Errors will not sit

well in the blithe pointlessness of farce, how will it be allowed the

serious

points it seems determined to make without depriving it of its

essential

character, which is comic? “Serious” readings of the play have tended

to lose

sight of its comic dimension. In Barbara Freedman’s Lacanian

interpretation,

for example, the Comedy tantalizingly offers an

“allegory” of psychic

division and integration: it can “be read as a play with and upon

redemption:

it demonstrates how one redeems (recovers) oneself by redeeming (making

payment

on) one’s debts as one redeems (goes in exchange for) one’s alter ego,

and how

one is thereby redeemed (released) from bondage only to share in the

fruits of

redemption (as rebirth).” This master narrative turns out to be only a

tease,

however, for “farce” ultimately “displaces meaning” and replaces the

“‘pure

sense of life’ celebrated by Western narrative comedy” with a mockery

of “the

ego’s interest in representations that suggest unity, purposiveness,

and

integrity.”[46]

Patricia

Parker, like Freedman, finds in the play “fragmentation,”

“multiplicity” and an

indeterminacy that frustrates a reader’s desire for order and holistic

meaning.

But she places the play’s “disjunctions” in historical contexts rather

than in

relation to “a panhistorical experience of Lacanian méconnaissance.”

What she finds incompatible are the play’s dense tissue of biblical

allusions,

generally pointing to the Protestant version of salvation history

culminating

in the Redemptive Apocalypse, and the action’s firm setting in the

world of the

marketplace, where the “metaphorical language of debt and redemption on

which

the Church’s master narrative depended” was becoming inadequate to the

slippery

realities of “social exchange and verbal coinage,” in a theater of the

world

“whose meanings were contradictory and unstable.” The Comedy

then is

read as a “post-Christian” drama in which the bible becomes only “a

source of

metaphors for dramatic structure, detached from belief and homiletic

piety.”[47] These

interpretations, committed to and

directed by sober deconstructive formulas, either turn comedy sour or

ignore it

altogether. They discern in the play an allegorical impulse, which they

define

only to proclaim misleading. A more straightforward allegory has been

read into

the work by Donna Hamilton, whose Shakespeare and the

Politics of Protestant

England finds the playwright consciously engaged with the

“church-state

politics” of his time, in The Comedy of Errors as

elsewhere. The

“historical context” out of which she supposes the Comedy

to have been

written is much more specific than Parker’s early modern “marketplace.”

It is

the conflict between the political and ecclesiastical authorities of

the

English state-church and the nonconformist Protestants whom the

Elizabethan

Settlement had left unsatisfied. In traditional allegorical terms,

Adriana is

said to represent the established English church, wrongly accusing her

husband

Antipholus (the nonconformist) of infidelity. The play’s physical

violence is

seen as a theatrical “literalisation” of the language of violence

spewed out in

the Marprelate controversy, now presented “in such a way as to display

hierarchy senselessly victimizing the disempowered.” The comedy’s

resolution,

bringing the state’s ruler and an entire family together within the

bosom of a

“church,” proposes a model of ecclesiastical unity different from the

“status

quo,” a new order in which “brother and brother” walk “hand in hand,

not one

before another” (5.1.425-6), suggesting an abridgement of hierarchy’s

privileges. Comedy is thus given its due as “parodic” criticism as well

as

tendentious idealism. And Shakespeare emerges from Hamilton’s study as

a

tolerant liberal “opposing absolutist tendencies.”[48] This analysis

is rife with difficulties. It

discovers a sustained allegory while making use of only a small number

of

characters and details that might underlie it. Ignoring the play’s

Catholic

setting and allusions, it arbitrarily chooses the lay and rather

helpless wife

Adriana to represent the authoritarian English church, leaving unclear

her

relationship to the Abbess Aemilia, an explicitly authoritative (and of

course

Catholic) ecclesiastical figure who supersedes the jealous wife’s

(church’s?)

authority without being shown to “represent” anything. The

“nonconformist”

Antipholus, wrongly accused of infidelity and thus allegorically a

victim of

misguided religious authoritarianism, is yet one of the drubbers who

perpetrate

the violence that victimizes the “disempowered,” a class to which the

allegory

would have him belong. Hamilton’s

instinct seems sound, however,

that in The Comedy of Errors Shakespeare undertook

to speak

serio-comically about divisive social, political, and religious ideals.

As we

have seen, the shadow of religious (disguised as mercantile) warfare

looms over

the play from its beginning. In its gray light, the zany “errors” of

accident

and comic misprision may remind a sensitive audience that “Error” of a

different kind, religious and grandiose, has invited the sword that

keeps apart

wife and husband, brother and brother. As a number of recent

commentators on

the Comedy have observed, Paul’s exhortations to

the Ephesians, which

Shakespeare has resolutely insinuated into the play, were not only to

domestic

love and harmony, but to a unity that transcended the largest and most

formidable of boundaries. Freedman and Parker have stressed the

relevance to

the Comedy of Ephesians 2, which proclaims the

salvation of Gentile and

Jew alike and the unity of both in Christ: For [Christ] is our peace, which hath made of

both one, and hath broken

the stoppe of the partition wall . . . that he might reconcile both

into one

body by his crosse, and slay hatred therby. . . . Now therefore yee are

no more

strangers & forreiners. . . .[49] Arthur Kinney

has

found equally relevant passages in Ephesians 4: There is one body, and one Spirit . . . There

is one Lord, one Faith,

one Baptisme, One God and Father of all. . . . we [shall] all meete

together in

the unitie of faith . . . unto a perfit man . . . let not the sunne goe

downe

upon your wrath . . . Let all bitternesse, and anger,

and wrath, crying, and evill speaking bee put

away from you. . . .[50] The sun does

not

go down on the wrath of the Ephesians and Syracusans in The

Comedy of Errors.

In compliance with biblical ideals as well as with the neo-Aristotelian

prescription of temporal “unity,” the final scene takes place when the

“dial

points at five” (118) just before the happy resolutions and reunions.

The

conclusion, celebrating the re-establishment of family ties more than

the

fulfillment of personal desires,[51]

also, under the religious auspices of the Abbess, reconciles Ephesian

ruler,

“merchants,” and citizens with the men of Syracuse whose blood the

“rigorous

statutes” of both “towns” had been designed to spill. Is it

legitimate to think here, along with

Paul’s desire for unity between Jew and Gentile, of Shakespeare’s

vision of

reconciliation between Protestant and Catholic? We have already seen

enough of

his interest in religious controversy to judge that such an idea is not

incredible. Nor is the thought too heavy to derive from a play like the

Comedy

which relies extensively not only on texts that are cleverly daft but

on

Scripture, the earnest prose of a Jesuit missionary, and the tragic

history of

the times. Yet why should such a solemn issue be subjected to what

might seem

the indignities of comic treatment? Why should many of the zealous

words of

Paul and Southwell be placed (as they are) in the mouths of the

clownish

Dromios? The ideal of political and religious unity cannot be said to

emerge in

a “darke conceit” of allegory that flows beneath the comedy. Egeon may

seem

allegorically a priestly merchant, but other merchants in the play seem

only

businessmen; the bloody statutes may summon up thoughts of an

historical

allegory, but in such a narrative the Duke and the Abbess would be on

unhistorically good terms, since the priory sits untroubled in Ephesus;

the

Antipholi are brothers kept apart but not, as they would be in

religious

strife, alienated. Critics are

sensible to see in The

Comedy of Errors, however cunningly crafted it is, fragments

of thought,

conflicting tones, resolutions that feel partial or have no right to be

true.

But they are wrong to see in these features the irresponsibility of

farce.

Farce, says Freedman, is “just the opposite of a . . . fantasy of wish

fulfillment, and in this sense opposes the adaptive functions of both

dream and

comedy.”[52]

The

Comedy of Errors seems in fact more than anything else

a public

exercise in wish fulfillment. The dream it dreams is not an allegorical

vision

(which is no dream at all) but a patchwork of ideals that slip in and

out of

tragedy, in and out of hilarity and weirdness. Its characters need not

all nor

always be emblematic, for the constancy is in the wish, not in the

figments

that embody it. The wishful idealism is real. It is also irresponsible,

but

only because brute facts are too hard against it. To treat the ideals

with

frivolity is neither to deny their worth nor to escape from them, but

to keep

them alive in a part of the imagination where cruel and sober censors

(whether

psychic or political) will hardly bother to look. To place them

in a world both sad and silly

is also to admit that waking as well as dreaming is so. A pure idealism

must

contend with this fact, especially that ideal of domestic and religious

peace

which Paul fervently preached to the Ephesians and which seems to be

embodied

in the play. In the world to which Shakespeare’s Comedy

was addressed,

the Pauline hope might seem a preposterous wish, whose fulfillment was

fatally

threatened by the fierce, even vicious certainties of religious

competitors, by

the confusions of identity which religious conflict as well as accident

might

produce, and by the follies of love and lovers--all of which bespeak

something

of the tragi-comic “madness” that the play’s characters continually

find in one

another. That such madness disappears too easily at play’s end in a

festival of

recovery, renunion, and reconciliation has led suspicious commentators

to

challenge the completeness of the comic achievement, as they note that

one

marriage is left only doubtfully reconstructed and another one only an

indefinite possibility.[53]

Yet

it is possible to assume that “at its ending The Comedy of

Errors admits

its own artificiality, its participation in [the] special realm of

fairy tale,”[54]

not

in order to offer ironic criticism of things as they are, but to hope

with a

deliberate foolishness that they might be better. And from the

play, what might Southampton

and the Catholics at Gray’s Inn have inferred was a “better” politics?

That the

bloody policies of both “synods” (1.1.13) might be

terminated. That

Catholic “merchants” not be considered criminals by virtue of their

mere

presence on English soil. That the false demonizings and vain

exorcizings of

the misunderstood “other” might cease. That the state might live in

concord

with a “mother” church that would have, like the Abbess in the

territory of

Duke Solinus, a site of its own authority. And that she might freely

speak, as

Aemilia does, “Whoever bound him, I will loose his bonds”

(5.1.340)--words

which would remind Catholics above all of Christ’s committing of the

“keys” to

Peter with the promise, “whatsoever thou shalt binde upon earth, shall

be bound

in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose on earth, shall be loosed in

heaven”

(Matt. 16:19). In the years following the Armada, hopes for Protestant

accommodation with Catholics on such terms were as fantastic as the

“fairy

tale” ending that Shakespeare created in the knowledge that it would be

recognized as such. Neither the English government nor Catholic

authority

represented by Robert Southwell was as conciliatory as Shakespeare’s

play; but

there was an audience for stories of wild unlikelihood like this one,

an

audience who knew how to find in the unsystematic and comic

presentation of a

religious sub-text political fancies that they were glad to entertain

as

anodynes for distress. Shakespeare of course wrote not only for

spectators such

as these, yet he had professional and personal incentives to keep them

in mind. II The Comedy of

Errors was performed at Gray’s Inn on December

28, 1594; that is, on the feast of the Holy Innocents, children who

according

to the Gospel of Matthew were victims of Herod’s savagery and in Robert

Southwell’s mind the first Christian martyrs (Matt. 2:16-18; “The

flight into

Egypt,” 13-18). Shakespeare’s

fantasy of

wish fulfillment forestalls martyrdom, but only through a Duke’s

arbitrary

decision to refuse a ransom and suspend the law, which in the final

common

happiness is not changed (Err 5.1.390-91). For those

who did not live in

a comedy and whose consciences made them liable to the cruelty of

magistrates

and laws that art’s magic could not attenuate, Shakespeare also had in

his

repertoire a different kind of martyrial drama, one that did not

imagine

redemption. It too offered only partial truths, but different and

unconsoling

ones, about the condition of those facing the threat of religious”

violence.

Its comedy was brutal rather than benevolent, portraying a culture of

martyrdom

nowhere informed or supported by love or any other genuine religious

impulse.

Shakespeare saw fit to publish this other piece in 1594, perhaps to

capitalize

on its great popularity as a work for the stage, perhaps to add to the

portfolio of works on personal, political, and religious themes that he

had put

together in that year. Titus Andronicus, as the title

page of the First Quarto

indicates, seems to have been written first for performance by the

players of

the “Earl of Darbie,” or Ferdinando Stanley, Lord Strange (who assumed the more exalted title in

1593).[55]

Like Southampton, Derby was guarded in expressing his religious

opinions; but

he was based in Catholic Lancashire, had numerous Catholic relatives,

and was

thought by some Catholics to be sympathetic to their cause.[56]

As Andrew Gurr has suggested, it is likely that playwrights of

Shakespeare’s

time were sensitive to the “religious allegiance” of their companies’

patrons.[57]

A

reading of Titus from a political and religious

perspective will show it

to have contained a great deal to interest an ambiguously Catholic

Derby, and

at least as much to intrigue the conflictedly Catholic Southampon. Scholarship has

found in Titus a

“larger number of significant parallels [with] Venus and

Adonis and The

Rape of Lucrece, especially the latter, than [with] any other

works of

Shakespeare.”[58]

Similarities in subject and language between Titus

and Lucrece

are often adduced in arguments about the play’s date of composition,

but they

may point to meaning as well as fact. If the “subject” of Lucrece

is as

surreptitiously ideological as has been proposed in this study, its

affinities

with the play should alert us to elements in Titus

that may be fraught

with the same kinds of significance. Titus Andronicus

is gory like a public execution; it

is imbued with the politics of religious warfare as well. A most

striking piece

of evidence about its political character resides in a scene which has

seemed

to many little more than comic relief[59]--even

though it ends with a clown’s being dragged off to the gibbet. By the

fourth

act of the play, Titus has a mind as steeped in blood as any of

Shakespeare’s

other characters. An inveterate soldier, he has lost more than twenty

of his

sons in warfare and has killed one of them himself. He has ordered the

ritual

sacrifice of a son of his enemy, an action that prompts a cycle of

revenge and

counter-revenge. Two of his own sons have been executed for a murder

they did

not commit. His daughter has emerged from a wood, “her hands cut off,

and her

tongue cut out, and ravish’d.” Titus has given up one of his hands in a

vain

attempt to save the lives of his falsely accused boys. When he learns

that his

daughter has been raped and mutilated by the sons of the Empress, the

Goth

Tamora, he becomes desperate for “justice,” but in such an antic way

that he

turns into an impresario of comic horror. One of his most puzzling

schemes is

to send a message to the Emperor Saturninus through a “Clown,” who had

been

going, with pigeons in hand, to one of the tribunes of the people to

settle a

domestic dispute. Titus diverts him: Tit.

Sirrah, come hither, make no more

ado,

But give your pigeons to the Emperor. By me thou shalt have justice at his hands. Hold, hold; mean while here’s money for thy charges. Give me pen and ink. Sirrah, can you with a grace deliver up a supplication? Clo. Ay, sir. Tit. Then here is a supplication for you; and when you come to him, at the first approach you must kneel, then kiss his foot, then deliver up your pigeons, and then look for your reward. I’ll be at hand, sir, see you do it bravely. Clo. I warrant you, sir, let me alone. Tit. Sirrah, hast thou a knife? Come let me see it. Here, Marcus, fold it in the oration, For then hast made it like an humble suppliant. (4.3.102-117) When the Clown

approaches Tamora and then Saturninus with letters and pigeons, the

Emperor

reads and immediately orders his guard to take the suppliant away “and

hang him

presently” (4.4.45). It is quite

probable that Shakespeare found

inspiration for this strange episode in the story of Richard Shelley, a

Catholic layman who, in 1585, put into Queen Elizabeth’s hand “at such

time as

she walked in her parke at Greenewitch” a petition on behalf of his

persecuted

co-religionists, and for his efforts “was promptly thrown into prison

by [the

Queen’s minister] Walsingham and left to die there” without trial.[60]

Shelley was the third son of John Shelley of Michelgrove, Sussex,[61]

and

Robert Southwell’s first cousin, once removed; Richard was related (by

his

sister’s marriage) to the Gages and to the earls of Southampton, and

through

his great grandmother, Alice Belknap, distantly by blood to Shakespeare.[62]

Southwell referred to his cousin’s fate in his own attempt at such a

petition,

a pamphlet written in late December of 1591. Its title was An

Humble

Supplication to Her Majestie, its purpose to defend English

Catholics

against scurrilous accusations made against them by a government

proclamation

and to protest against the unjust treatment of Catholic clergy and

laity under

the regime’s penal laws. One is immediately struck by the parallel

between

Shelley’s and the Clown’s naive and hapless innocence in delivering

their

messages (both asking for redress of grievances), by their similar

fates, and

by the apparent allusion to Southwell’s piece in Titus’s “supplication”

and “humble suppliant.”[63]

But

there is much more to connect the play, the pamphlet, and the political

context. When the Clown

wishes on Empress and

Emperor the blessings of “Saint Steven” (4.4.42), he unwittingly

associates

himself with the Christian protomartyr (Acts 7: 55-60). When he swears

“by

[our] Lady” (48), he evokes a Catholic world which like the anachronism

in Lucrece

seems deliberately, at various points, worked into the play’s pagan

Roman

setting. Titus prays to Jupiter and Pluto, sends his sons across Styx,

imagines

diving into Acheron, and sanctions human sacrifice to infernal manes

(4.3.13-54; 1.1.96-103). But his world also features, besides the

Clown’s

saints, “priest and holy water” for wedding ceremonies (1.1.323),

“hermits in

their holy prayers” (3.2.41), “popish tricks and ceremonies” (5.1.76),

“limbo”

(3.1.149), and a “ruinous [that is, “ruined”] monastery” (5.1.21). The

word

“martyr” and its cognates appear in Titus more than

in any other work of

Shakespeare; and there are signs that he intended them to have a

special

significance for his contemporaries, especially for those who would

have had an

interest in, even if they had not been able to read, Southwell’s Humble

Supplication. The

influence of the Jesuit’s petition on the play is discernible in more

than in

the similar fates of Shelley and the Clown. Just before the Clown’s

fatal

mission, Titus, pretending to ask for justice from the heavens, had

messages

sent to the Court on arrows, one of which had gone into “Virgo’s lap”

and

another “beyond the moon” to Jove himself (4.3.65-67). The vision here

is

doubled. “Virgo” is both Astraea (the goddess of Justice who has left

the earth

[4.3.4]) and the decidedly unvirginal and wicked Empress Tamora (in the

Court

where the arrows really land); “Jupiter” is both god and the undivine

Emperor

Saturninus (who in the next scene enters carrying the shafts in his

hand).

Southwell seems to have suggested to Shakespeare at least part of these

theatrics.[64]

Defending “Priests and Catholiques” against the vilifications of

government

word-smiths, which he compared to “arrows” shot at the innocent,

Southwell

warned the Queen that because of their outrageous messages those same

“arrows

[might] hit [her] Majesties honor in the way” (2). That is, they might

land in

the lap of the “Virgin Queen,” and (to continue with Shakespeare’s

image, which

implies what Southwell says later in his essay) would certainly travel

beyond

the “moon” (Elizabeth as the virgin “Diana” or Ralegh’s “Cynthia”) to

God

himself, who knew the injustice of their accusations. Southwell

pleaded with Elizabeth that she

show herself on earth an agent of justice at least, and more, a source

of

mercy. He liked to believe that she measured her “Regality more by will

to save

then by power to kill” (25). The idea (a common one, of course) is

paralleled

in Tamora’s early prayer to Titus that he “Draw near [the gods] in

being

merciful: / Sweet mercy is nobility’s true badge” (1.1.118-119). More significant,

Elizabeth was addressed by

the politic Jesuit as a “mighty . . . Princesse

. . . the only shoot-anker

of our last hopes,” (1). The Gothic-Roman ruler was styled, even by a

vengeful

Titus, as a “proud empress, mighty

Tamora”; she wished to have

rather than to be an “anchor” in a stormy world

(4.4.38). The Jesuit

describes his fellow Catholics as “at the bottome of

a helples misery”

(1), just as Titus complained that his “sorrow” was “deep, having no

bottom,”

there being no reason for his “miseries” (3.1.216,

219). A list of

simple verbal echoes, mere quirks of memory, might be extended.[65]

There are, however, more impressive and intriguing parallels than

these,

pointing to political issues that Southwell considers openly but

Shakespeare

only in dramatic obliqueness. Well into his

supplication Southwell

recalls that the first British ruler to be converted to Christianity

was “King

Lucius,” and laments that after the fourteen hundred years since his

time, in

which Catholic Christianity had flourished in England, “all Monasteries

[were] now . . . buried in their owne ruynes” (29).

The play’s “ruinous

monastery” (5.1.21) of course comes to mind, but more

important, Titus’s

son Lucius, who becomes Emperor in the final scene. Shakespeare’s

Lucius is a

warrior from ancient Rome, and at the same time a Roman Catholic. The

atheistic

villain Aaron is willing to accept Lucius’s promise to save his child

because,

as he says,

I know that thou art

religious,

And hast a thing within thee called conscience, With twenty popish tricks and ceremonies, Which I have seen thee careful to observe. . . . (5.1.74-77) (Compare

Southwell’s emphasis on the moral fastidiousness of English Catholics,

which

their enemies were alert to take advantage of: “many that see, are

willing to

use the awe of our Consciences for their warrant to tread us downe”

[26].) Why the

telescoping of centuries and the

blurring of distinctions between antique and contemporary “Romans”?

Jonathan

Bate has argued that a “Reformation” theme is embedded in the play, a

theme

meant to illustrate the concept, as Samuel Kliger has studied it, of

the translatio

imperii ad teutonicos (the transfer of empire to the German

peoples): The translatio suggested

forcefully an analogy between the

breakup of the Roman empire by the Goths and the demands of the

humanist

reformers of northern Europe for religious freedom, interpreted as

liberation

from Roman priestcraft. In other words, the translatio

crystallized the

idea that humanity was twice ransomed from Roman tyranny and

depravity--in

antiquity by the Goths, in modern times by their descendants, the

German

reformers.[66] At a time, Bate

declares, when Elizabeth’s age and childlessness had made “the issue of

succession”

most urgent, and “the preservation of the Protestant nation” a deep

concern,

Shakespeare wrote into his play a form of reassurance: The Goths who

accompany

Lucius into a Rome that is really England “are there to secure the

Protestant

succession,” to ensure that the monasteries would stay ruined, and that

no more

Lavinias would be mutilated to provide matter for another Foxe’s Book

of

Martyrs.[67] Although there

may be good reasons for

imagining the Goths as Protestants, it is difficult to credit this

interpretation of their role in the play. One can hardly forget that

the Goths