|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

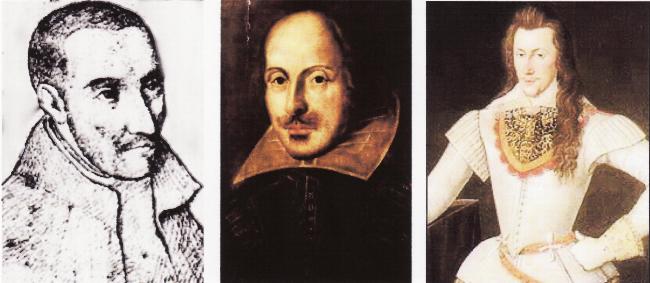

SHAKESPEARE, THE EARL AND THE JESUITJohn Klause |

|||||||||||||

CONCLUSION

This study,

which began with the promise of

biography, has told no detailed story. Although it moves through time,

refers

to history, and speaks of personal and political change, a narrative

rich in

circumstance is beyond its reach. What has been discovered are discrete

facts,

potentially correlative, that enlarge the area of inquiry for serious

searchers

who question the assumption that we shall never learn anything more of

significance about Shakespeare than is already known. New readings of

his works

have been attempted, open to the possibility that he experienced the

anguish of

conscience which many of his contemporaries felt as the world of faith

divided

itself into worlds at war. The facts might well be summarized now,

distinguished from the speculations into which they shade, and weighed

for

their suggestive value. The most

obvious and the most certain

conclusion to be inferred from the preceding essays is that Shakespeare

“knew”

Robert Southwell: possessed his works, almost all of them; had them so

densely

yet broadly folded into his memory that they could become, like the

bible for a

dévot, instantly and bountifully available at the slightest hint of

their

relevance to his task at any moment of composition. Such moments of

influence

were remarkably frequent, suggesting both the author’s extended memory

of

Southwell’s texts and his rereading of them. Instances can be observed

throughout the poetry and drama that we have examined, works that for

more than

a decade seem to have addressed special concerns of the earl of

Southampton.

Indeed, the influence of Southwell on Shakespeare can be shown to

extend much

beyond the signs of it in these poems and plays.[1]

It is also clear that Shakespeare must have had access to Southwell’s

work

through secret and privileged channels, since the poet and playwright

made use

of a prohibited book (The Epistle of Comfort) and

manuscripts

available

only in close circulation in the Catholic underground. Shakespeare may

have

obtained them, as someone who could be entrusted with precious

contraband (and

here conjectures begin), from any number of his Catholic relatives or

connections, perhaps even from Southampton, who was an enthusiastic

collector

of Catholic literature even late into his life, when he publicly

identified

himself as a Protestant. It is also

possible that Shakespeare could

have received Southwell’s writings from his Jesuit “cosen” himself.

There is

hardly any reason to doubt that Southwell sent copies of his poems to

his

kinsman “W.S.,” who had “importune[d]” the author to write them, and

from whom,

in return, the author had asked for help in producing better “Musicke.”[2]

Was

“W.S.” William Shakespeare? Even before it could be claimed that

Southwell’s

writings had Shakespeare in their grip, there was no other known

plausible

candidate. Now, with a significant literary relationship between the

two men

established, the possibility that Shakespeare was the addressee is

greater by

many degrees. And yet if we are to assume the identification, we must

also suppose

that Southwell did not fully appreciate the differences of temperament

and

principle between himself and a cousin who would not only defy an

exhortation

to prefer Christ to Venus as a literary subject, but would spend years

responding to the gifts that had been given him by his martyred

relative as an

adversary as well as a friend. Whether Shakespeare was acquainted

personally

with Southwell or not, he could not let go of, nor could he acquiesce

to him. Herbert

Thurston, the Jesuit who

demonstrated that Cardinal Borromeo’s Testament of the Soul

was

the

basis for what may be John Shakespeare’s Spiritual Testament,

was quite

wary about attributing anything but “a Catholic tone” to William

Shakespeare’s

mind, and perhaps a sympathetic and tender feeling “about the creed in

which

his father and mother had been brought up.” Thurston could not ignore

what he

believed to be Shakespeare’s accommodation to the demands of the

English

state-church, nor “the loose morality of the Sonnets, of Venus

and

Adonis,

etc. and of passages in the plays.” He wondered about Shakespeare’s

“atheism,”

finding that a “number of Shakespearean utterances expressive of a

fundamental

doubt in the Divine economy of the world” seem to go “beyond the

requirements

of his dramatic purpose and . . . are constantly put into the mouths of

characters with whom the poet is evidently in sympathy.” Prospero’s

musing, for

example, that “life / Is rounded with a sleep” was theologically

suspect.[3]

The

late-Victorian Jesuit, strict in his sense of orthodoxy, narrow in his

hermeneutics, and perhaps oversensitive to indications of misbelief,

could not

approve of, much less tolerate, the ambiguous or skeptical “utterances”

of

Shakespeare, nor the poet’s apparent nonchalance toward moral and

credal

imperatives. Elizabethan and Jacobean Christians, however, both

Protestants and

Catholics, may well have approached their crises of faith in ways that

have

become difficult for their descendants to comprehend. Shakespeare the

“sinner”

may have found extraordinary ways to condemn and forgive himself for

“Th’

expense of spirit in a waste of shame”; his Lear-like challenges to the

gods

could have meant that he took deity seriously enough to be pained and

perplexed

by its silence, its invisibility, and its apparent indifference to

triumphant

evil. The Shakespeare who emerges from this study shows no strong signs

of

preference for specific doctrines that divide one faith from another;

perhaps

he was of a mind with Lucio on at least one point, that “Grace is

grace, despite

of all controversy” (MM 1.2.25). Yet, uncommonly

knowledgeable

of things

Catholic, he is quite intent on creating Catholic worlds in poetic and

dramatic

spaces, both where one might expect such an environment (medieval

Denmark,

“modern” France, Italy, and Vienna) and where one might not (ancient

Rome,

ambiguously antique Ephesus). He does so not merely for art’s sake, but

to

dramatize experiences and explore issues that arise in a Catholic

situation,

which he does not fear to present with sympathy as well as criticism.

He shows

every sign of sympathetic interest in the torments of conscience, good

conscience and bad, that divide human beings from one another. His

interest in

civil war, brother against brother, sustained as it is throughout his

career,

from Henry VI to The Tempest,

is therefore not an

inexplicable

obsession but an outgrowth of his sensitivity to the religious conflict

that

Robert Southwell and Henry Wriothesley helped define for him. The author of a

book on “Shakespeare’s

Religious Frontier,” who like most scholars wrongly assumed that

Shakespeare

had read in his life only “once piece of polemical divinity”

(Harsnett’s Popish

Impostures), believed that the poet’s response to religion at

war

with

itself was an

“incomparable aloofness

from all partisan religious issues.”[4]

Yet

Shakespeare was not so olympian that he could view such contention with

a

happily suspended judgment. Church and state were for him individual

human

beings, not merely abstractions. Those who punished religious deviance,

the

deviant who suffered punishment, and those who evaded punishment by

hiding or

avoiding deviance were all liable to assessment. This estimate, which

extended

beyond the axioms of religious or legal casuistry, was harsh or

compassionate

depending on the moral intuition of a judge (Shakespeare was a judge!)

as

radical and discomfiting as the Sermon on the Mount could make him. From

such a perspective Shakespeare considered the dilemmas of his patron

and friend

Southampton, who was linked to him as to Southwell by family ties and

by a

sense of what constituted momentous choice in the matter of religious

allegiance. This claim is of course speculative, but not, in light of

limited

but suggestive evidence, unwarranted.

It

is reasonable to believe, as has here been argued, that all three men

understood Catholicism as the far from uniform practice of the

Catholics they

knew. The priest wished more uniformity; the two laymen were content

with less,

revealing, unlike their cousin, a flexibility in religious politics

that need

not be called indifference to its underlying principles. Whether or not

Shakespeare and Southampton had “tender feelings” for the Catholic

faith of

their fathers and mothers, they knew the strong chances of suffering

for it.

The patron and his poet were aware that the persecutors were far from

righteous, but also that the persecutorial spirit lived everywhere in

“Christian” Europe. Towards the Lucretias and the heroic nuns of the

world,

“thrice blessed” but sometimes “self-loving,” they were ambivalent;

towards the

Tarquins, Tituses, and Tamoras, they were hostile. Like Southwell,

Shakespeare

was willing, in Hamlet, to view politics in the

light of

transcendence;

but such a consideration could not tell Southampton, or others stricken

with a

sense of the world’s privileged and protected injustice, what to do or

not to

do about it. When Southwell was long dead and Southampton had moved

farther

then ever from importunities of Counter-Reformation missionaries,

Shakespeare

used the Jesuit’s words to imagine for the earl whose trespasses had

been

forgiven how an old fantasy of religious reconciliation (in the Comedy

of

Errors) might be succeeded by a new one (in Measure

for Measure)

with a better chance of being at least partly realized--if only a new

prince of

peaceable temper could be persuaded to seize it. James missed

this opportunity. The

Gunpowder Plot would defer indefinitely hope for another chance.

Southampton,

again in Parliament after his pardon, might have been among those

killed had

the powder conspirators succeeded.

He

had been given no warning, though some of his relatives (and

Southwell’s, and

Shakespeare’s) were involved in the plot. Yet he did not turn his back

entirely

on his former co-religionists, continuing to help some of them in their

need.

Shakespeare, of course, alluded to the conspiracy in Macbeth,

singling

out the “equivocator” Jesuit Henry Garnet for special opprobrium. As he

wrote

this play, however, Robert Southwell was still in and on his mind. That

“fact”

and many others are matters requiring new contexts for discussion. C’est

toute une histoire. NOTES To Conclusion

[2]. McDonald and

Brown, eds, Poems

of

Robert Southwell, 1-2.

[3]. The

Catholic Encyclopedia,

s.v.

“The Religion of Shakespeare.”

[4]. Stevenson, Shakespeare’s

Religious

Frontier, 62, 80.

|

|||||||||||||

| Copyright © John Klause 2013. |