|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

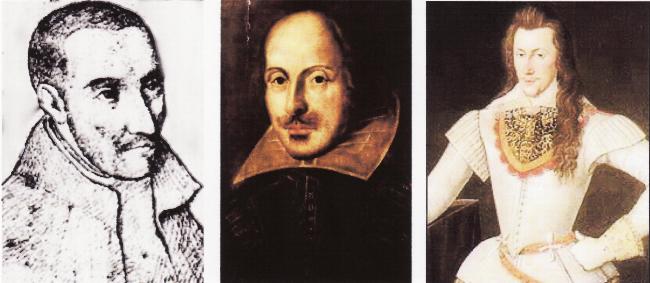

SHAKESPEARE, THE EARL AND THE JESUITJohn Klause |

|||||||||||||

|

CHAPTER

5 All’s

Well that Ends Well Is it true, as Sonnet 107,

which scholarly opinion now

with greater and greater assurance dates at the beginning of the reign

of King

James,[2]

has

no likelier purpose than to celebrate the earl of Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul Of the wide world dreaming on things to come, Can yet the lease of my true love control, Suppos’d as forfeit to a confined doom. The mortal moon hath her eclipse endur’d And the sad augurs mock their own presage, Incertainties now crown themselves assur’d, And peace proclaims olives of endless age. Now with the drops of this most balmy time My love looks fresh, and Death to me subscribes, Since spite of him I'll live in this poor rhyme, While he insults o'er dull and speechless tribes; And thou in this shalt find thy monument, When tyrants' crests and tombs of brass are spent. The “mortal

moon,” Elizabeth, has died and left behind her tyrant’s crest; despite

fears

and prophecies that her death would result in civil war, a new “age” of

peace has

been inaugurated; the balm that anointed a new ruler at his crowning

has with

its drops given “fresh” life to one whose “confined doom” had

threatened

forfeiture of love and life.[3]

As

well as looking forward, the poet looks back to “fears” and misguided

prophecies--and, perhaps hoping that We need not

assume that the new writing

ended with this poem. Looking at the plays that Shakespeare produced

soon after Akrigg

suggested a number of ways in which

Shakespeare could have had These

correspondences are intriguing; but All’s

Well is most strikingly relevant to To search those

purposes requires first

that we consider All’s Well as a set of

recapitulations. Although

Shakespeare often repeats himself, he seems in this play to have

deliberately

planted numerous traces of his former writings, as though offering a

new gift

that contained recognizable parts of old presents. In a single scene,

for

example, he reaches back across a decade to introduce names from the

past:

“Sebastian [Twelfth Night] . . .

Corambus [Hamlet, Q.1,

Corambis] . . . Jaques [As You Like It] . . .

Ch[ris]topher [Taming

of the Shrew], Vaumond (Hamlet, Voltemand)

. . . Dumaine [Love’s

Labor’s Lost]” (4.3.162-76). Elsewhere in All’s Well

we find Rinaldo

(3.4.19; cf. Hamlet’s Reynaldo), the mysteriously

silent “Violenta”

(3.5, s.d.; cf. Viola in Twelfth Night, named

“Violenta” in Folio 1,

1.5..166, s.d.), Antonio (one of Shakespeare’s favorite names) and

Escalus

(3.5.75-76; cf. Prince Escalus in Romeo and Juliet), Diana Capilet (5.3.147;

cf. Capulet in Romeo

and Juliet), and of course Helena (whose antecedents appeared

in both A

Midsummer Night’s Dream and, with “Cressid’s uncle,” Pandarus

[AW

2.1.97], in Troilus and Cressida). More than names

are recalled. Love’s

Labor’s Lost has a troop of false “Muscovites,” as does All’s

Well (LLL

5.2.121; AW 4.1.69). Both plays have sun-worshipers:

Berowne is one who

“like a rude and savage man of Inde,” bows his head and is blinded by

Rosaline’s heavenly majesty ; Helena confesses to being “Indian-like”

in her

idolatrous worship of Bertram, her “sun” (LLL

4.3.218-24; AW

1.3.204-6). Pandulph in King John argues the

invalidity of improperly

sworn oaths: “It is religion that doth make vows kept, / But thou hast

sworn

against religion, / But what thou swear’st against the thing thou

swear’st.”

Diana Capilet is no theologian, but she shares the churchman’s views on

swearing: “This has no holding, / To swear by Him whom I protest to

love / That

I will work against Him” (KJ 3.1.279-81; AW

4.2.27-29). In A

Midsummer Night’s Dream we hear of the “red-hipp’d

humble-bee”; in All’s

Well the “humble-bee” is also “red-tail’d” (MND

4.1.12; AW

4.5.6). Shylock tells us that some persons “are mad if they behold a

cat”;

Bertram is among them (MV 4.1.48; AW

4.3.237). Parolles, a lesser

Falstaff--liar, coward, corrupter of youth, and somehow pardonable--has

like

his predecessor a great scene in which the truth about him is exposed;

before

it he contemplates giving himself “some hurts” as Falstaff had done,

and saying

that he “got them in exploit” (1HIV 2.4.261-2,

309-11; AW

4.1.37-38, 4.3). In Henry V Captain Fluellen seems

much conversant with

“the true disciplines of the wars,” with “the ceremonies of the wars,

and the

cares of it, and the

forms of it”;

Captain Parolles, self-proclaimed “militarist,” professes to know the

wars,

“the whole theoric . . . and the practice” (HV 3.2.72,

4.1.72-73; AW 4.3.141-43).

Henry’s soldier Michael Williams, having been assured by the disguised

king

that the cause of war in The resonance

of Shakespeare’s earlier work

in All’s Well that Ends Well is

quite conspicuous in the

parallels between the play and the poems, especially the Sonnets and Venus

and Adonis. Critics have been especially struck by the

Sonnets’

anticipation of important elements of All’s Well.

Sheldon Zitner, like

others, has noted that [the] “I” of the Sonnets is himself a kind of

If she be All that is virtuous--save what thou dislik’st, A poor physician’s daughter--thou dislik’st Of virtue for the name. But do not so. (2.3.121-24) The love of the

poet is “religious,” almost unto “idolatry”

(31.6, 105.1); Sonnets All’s Well 6.13-14: 3.4.16: thou art much too fair He is too good and fair for death and me To be death's conquest 13.14 1.1.17-18: You had a father, let your son say so This young gentlewoman had a father--O, 24: 1.1.93-95 stell’d draw [his beauteous features] In our heart’s Thy beauty's form in table of my heart; table 27.5-6: 3.4.4-11 from far where I abide, I am Saint Jaques' pilgrim . . . . Intend a zealous pilgrimage to thee I from far His name with zealous fervor sanctify 31.9-10: 2.3.138-39: the grave . . . on every grave Hung with the trophies A lying trophy 42: 1.3.46-50: Thou dost love her, because thou knowst I He that comforts my wife is the cherisher love her, of my flesh and blood; he that cherishes my And for my sake even so doth she abuse me, flesh and blood loves my flesh and blood; he Suff’ring my friend for my sake to approve that loves my flesh and blood is my friend: her. ergo, he that kisses my wife is my friend . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . But here's the joy; my friend and I are one; Sweet flattery! then she loves but me alone. 64.13-14: 1.3.214-16: This thought is as a death, which cannot her whose state is such that cannot choose choose But lend and give where she is sure to lose But weep to have that which it fears to lose 115: 3.4.18,21: blunt the sharp'st intents, what sharp stings . . . Divert strong minds . . . . . . . . . I could well have diverted her intents 129.2-5: 4.4.24-25 lust in action . . . Is . . .despised . . . so lust doth play With what it loathes 135.5-6: 4.3.16-17: Wilt thou, whose will is large and spacious, he fleshes his will in the spoil of her honor Not once vouchsafe to hide my will in thine? We cannot be

sure what part the Sonnets

played in the relationship between Shakespeare and Southampton. If the

poet

addressed pieces to the “friend” as verse letters (comparable to

Donne’s verse

epistles to his friends), not all of them may have been “sent.” There is so much

repetition in the Sonnets,

so much that sounds like private complaint which the speaker only

imagines

making public, so much that is impolitic or even insulting, that they

seem like

journal entries which may on occasion have turned into messages. If the

poems

were part of a fiction that derived inspiration or incident from life,

and as

such were (according to the testimony of Francis Meres in 1598) passed

around

to Shakespeare’s “private friends,” among whom Southampton may have

been

numbered, the earl may have had for any number of reasons special

insights into

their meaning. It appears that the lyrics were composed in several

different

groups, with a range of different purposes, and across a long period of

time--from the early “Anne Hathaway” poem (145) to at least the

“Southampton”

sonnet of 1603 (107). What is proposed here is that the Sonnets,

whatever their

origins, became part of the large store of literary capital that

underwrote the

making of All’s Well that Ends Well, a play which

reminded the earl of

Shakespeare’s early declaration that “What I have done is yours, what I

have to

doe is yours, being part in all I have, devoted yours.” If Venus and Adonis All’s Well 203-4, 763-5, 752, 768: 1.1.136-44: O, had thy mother borne so hard a mind, To speak on the part of virginity, is to She had not brought forth thee, but died accuse your mothers; which is most unkind. . . . infallible disobedience. He that hangs So in thyself thyself art made away, himself is a virgin: virginity murders itself A mischief worse than civil home-bred strife, and should be buried in highways out of all Or theirs whose desperate hands themselves sanctified limit, as a desperate offendress do slay. . . . against nature. . . . Besides, virginity is Love lacking vestals, and self-loving nuns . . . peevish, proud, idle, made of self-love . . . . . . . gold that’s put to use more gold begets out with't! within ten year it will make itself ten, which is a goodly increase; and the principal itself not much the worse. Compare Venus

and

Helena as they solicit a kiss: Venus and Adonis All’s Well 723-4: 2.5.80-86: And all is but to rob thee of a kiss. I . . . Rich preys make true men thieves. . . . . . . like a timorous thief, most fain would steal What law does vouch mine own. . . . Strangers and foes do sunder, and not kiss. Compare Venus

and

a French Lord on life’s imperfect mixtures:

Venus and Adonis

All’s

Well

733-36: 4.3.71-72: And therefore hath she brib’d the Destinies The web of our life is of a mingled yarn, To cross the curious workmanship of Nature, good and ill together To mingle beauty with infirmities, And pure perfection with impure defeature. . . . There are many

other verbal likenesses, among them: Venus and Adonis All’s Well Dedication: 5-6: 1.3.44-45: I shall . . . never after eare so barren a land, He that ears my land . . . gives me leave to for fear it yeeld me still so bad a harvest inn the crop 5: 1.3.136: Sick-thoughted Venus [Helen’s] eye is sick on’t 25-26: 1.1.51: his . . . palm, takes all livelihood from her cheek The president of pith and livelihood 107: 3.3.9-11: [Mars’s] drum Great Mars . . . , . . . I shall prove A lover of thy drum 177-79: 2.1.161-62: Titan . . . , the horses of the sun shall bring With burning eye . . . , Their fiery torcher his diurnal ring Wishing Adonis had his team to guide 298: 2.2.18-19; Thin mane, thick tail, broad buttock the pin-buttock, the quatch buttock, the brawn buttock 256-263: 2.3.281ff: And from her twining arms . . . Spending his manly marrow in her arms, . . . . . . . . . . . . . Which should sustain the bound and high curvet Away he springs, and hasteth to his horse . . . Of Mars’s fiery steed The strong-neck’d steed [and 142, “marrow,” 219, “fiery”] 302: 5.2.232: he starts at stirring of a feather every feather starts you 500-1: 1.1.95-96: that hard heart of thine, heart too capable Hath taught them scornful tricks Of every line and trick 755-56: 1.2.58-59: the lamp that burns by night “Let me not live,” quoth he, Dries up his oil to lend the world his light “After my flame lacks oil. . . .” 804: 4.1.23: full of forged lies swear the lies he forges 821: 4.4.24: the merciless and pitchy night the pitchy night 1012-13: 2.3.137-39: she humbly doth insinuate; the mere word’s a slave Tells him of trophies, statues, tombs Debosh’d on every tomb, on every grave A lying trophy 1052: 2.1.43-5: Upon the wide wound that the boar had his cicatrice . . . on his sinster cheek; it was trench’d this very sword entrench’d it 1171-75: 5.3.327: She bows her head, the new-sprung flow’r If thou beest yet a fresh uncropped flower to smell, . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . She crops the stalk. . . . What likelier

purpose could all of these recollections serve than that of the poet’s

signalling a new artistic beginning created out of an old one, to

correspond

with the patron’s embarkation upon a new life? All’s Well retells the

story of Venus and Adonis after a

tumultuous decade for Southampton, who would see the original narrative

written

for him appropriately and therefore drastically revised. After flirting

with

disaster himself, he might welcome the transformation of the comic

tragedy into

a story in which all’s well that ends well. Probably the

last play that Shakespeare had

meant Love all, trust a few, Do wrong to none. Be able for thine enemy Rather in power than use, and keep thy friend Under thy own life's key. Be check’d for silence, But never tax'd for speech. (1.1.64-68) We soon learn

that Helena loves Bertram,

but sees him as “a bright particular star . . . above [her] sphere,” as

though

she had heard Polonius tell Ophelia, “Hamlet is a prince out of thy

star” (AW

1.1.86-9; Ham 2.2.141). The difference in rank will

not ultimately

matter for the young Frenchwoman, because she is shrewd and

strong-willed;

despite social protocols, the countess of Rossillion desires Hamlet continues to

appear in All’s Well beyond the

comedy’s first scene, and not just in the names of characters mentioned

in both

dramas. In both plays we hear of wrongdoers whipped or escaping

whipping, of

horses being wagered, of “woodcocks”

being caught, of “tragedians,”

and (as

nowhere else in Shakespeare) of the game of “hoodman-blind,” to which

Parolles

is actually subjected. From Venus

and Adonis, then, to Hamlet,

from a mythical-comical-tragical-pastoral poem to a

historical-comical-tragical

play, and through lyrics, histories, comedies, and tragedies that fell

in

between, Shakespeare ranged for material of his own that would help him

construct All’s Well that Ends Well. His

remembrance, however, would

have been drastically incomplete, on his own and on Southampton’s

behalf, had

it not included the written remains of Robert Southwell, which had

occasioned

so much of what Shakespeare had wished to say to himself and to his

patron. The

hidden conversation between Shakespeare and the earl often concerned

religion,

with Southwell’s words and thoughts the medium of exchange.

Shakespeare’s part

of the dialogue continued in All’s Well, and

through the same means. In All’s

Well, as in many of his

other works (The Comedy of Errors, The

Merchant of Venice, and Measure

for Measure, for example), Shakespeare introduces into an

essentially

secular narrative source a surprisingly large number of religious

references.

Usually the additions can be shown to serve specific purposes; but in All’s

Well they might seem particularly gratuitous. Why are there

appeals to the

remote power of “heaven” in explaining the King’s cure, when the

proximate

curative force of earthly medicine would seem sufficient for a story

that never

becomes religious in itself? Why are there allusions to contemporary

religious

conflicts between Papists and Protestants in a drama set in Catholic

France and The character

of All’s Well 1.1.82-98 MMFT My imagination 64r: imagination Carries no favor in't but Bertram's. 64v: favour I am undone, there is no living, none, If Bertram be away. 'Twere all one That I should love a bright particular star 61v: starres . . . Sphers And think to wed it, he is so above me. 64v: I must be contented to . . . take In his bright radiance and collateral light down my desires to farre meaner hopes, Must I be comforted, not in his sphere. sith former favors are now too high The ambition in my love thus plagues itself marks for me . . .O my eyes why are you . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . so ambitious . . . ? He is now too bright ’Twas pretty . . . a sunne for so weake a sight To see him every hour, to sit and draw [His likeness] In our heart’s table. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . My idolatrous fancy 58v: fansies Must sanctify his reliques. 66r: sanctified.[16] Marie too knew

of

“loves ambition” (MMFT, 28v).

Without her Lord, she

said, who was the “life of her soule. . . , any other life

would be death”

(cf. “no living, none, if Bertram be away”). The

image of her love Marie

“had limm’d in her heart,” a “Table”

which she feared to break,

and to which she had entrusted the last “relique” of

her happiness (MMFT

5r; and 13v: “it

is all one”). One

of the most painful moments in All’s Well is that

in which the newly

married In another

solitary meditation,

All’s Well 3.2.100-14:

EC

. . . no wife! . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Poor Lord, is’t I That chase thee from thy country, and expose 46r: exiled from her native country . . . Those tender limbs of thine to the event 40r: venture life and limme; 48r: if a Of the none-sparing war? And is it I younge spouse tenderlye affected, and That drive thee from the sportive court . . . deeplye enamoured upon her new husbande . . .to be the mark see him assaulted by . . . enemyes . . . , what Of smoky muskets? O you leaden messengers, a multitude of frightful passions oppresse That ride upon the violent speed of fire, her . . . Of every gun that is discharged, she Fly with false aim, move the still-[piecing] air[17] feareth that the pellet hath hitt his bodye. . . . That sings with piercing, do not touch my Lord. 45v-46r: with so many perils is our breast Whoever shoots at him, I set him there; assaulted . . . [our soul] exiled like a caytive Whoever charges on his forward breast, (also: 49v: warre 43r: dryven; 51r: I am the caitiff that do hold him to’t disporte; 37v: marke; 41v: fire; 37r-v: my Lorde . . . touchinge; 40r: I set him) Helena and

Southwell both present

themselves as physicians, one of the body, the other of the soul; they

both

risk “vildest torture” and the loss of their lives to perform their

service (AW

2.1.174); and they speak of their work in closely parallel terms. All’s Well 1.3.221-25, 242-45 Southwell my father left me some prescriptions EC, 89r: prescript Of rare and prov’d effects, such as his reading EC, 82r, 86v: rare . . . proofe . . . effectes And mainfest experience had collected EC, 88v, 90r: manifestly . . . experience For general sovereignty; and that he will’d EC, 85v: some medicines . . . have a generall me and common force aga[i]nst all [diseases] In heedfull’st reservation to bestow them. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . There’s something in’t EF, 5-6: I have . . . brought . . . medicinable More than my father’s skill, which was the receipts. . . . I have studied maladies and greatest medicines. . . . and make you a present of my Of his profession, that his good receipt profession. . . . EC, 87r: these [miracles] Shall for my legacy be sanctified surpass the habilitye of any creature. . To the King’s

initial refusal of He that of greatest works is finisher Oft does them by the weakest minister: So holy writ in babes hath judgment shown, When judges have been babes. . . . (AW 2.1.136-39) Southwell the

physician of souls is also a Daniel come to judgment: My desire is that my drugs may cure you. . . . Despise not . . . the youth of your son, neither deem that God measureth his endowments by number of years. . . . Daniel, the most innocent infant, delivered Susanna from the iniquity of the judges. . . . God revealeth to little ones that which he conceals from the wisest sages (EF, 5-6). It is not just

Helena who benefits from

Shakespeare’s recollection of Southwell. In his weakness, the brooding

King

feels that his “flame lacks oil”

(AW 1.2.59); Southwell

had used the same image (EC, 56v:

“the oyle, to

nourishe and feede his flame”). When the monarch is

restored to health,

his deficiencies turn into a superflux (as he sees it) of creative

power. “I

can create” a new Both the piety

of Lafew and the irreverence

of the clown Lavatch draw forms of expression from Southwell’s prose.

Lafew

states his belief in miracles, for example, in lines that might have

come from

the Epistle of Comfort: All’s Well 2.3.1-6: EC, 82r, 86v, 88v: They say miracles are past, and we have our Philosophers . . . went about to compasse philosophical persons, to make modern and our faith in their bare reason . . . God [is] familiar, things supernatural and causeless. the only author of these supernatural Hence is it that we make trifles of terrors, effectes . . . to doubte whether these ensconcing ourselves into seeming knowledge, [contemporary] miracles be true . . . is when we should submit ourselves to an only to allow that whereof our owne unknown fear. sight and sense doth acertaine us (and 169r-v: submit themselves unto . . . feare . . . terrifyinge)[18] In a bit of

verbal sparring with Lafew and

the countess (AW 4.5. 20-55), Lavatch has a mouth

full of the bible. He

is, he says, “no great Nebuchadnezzar,” for he has

“not much skill in grass”

(with a pun on “grace”; cf. Daniel 4:28-30). He serves the “prince

of

darkness, alias the devil . . . , the prince of the

world” (cf.

Ephesians 6:12). Yet in clownish inconsistency he claims to be “for . .

. the narrow

gate” that leads to heaven, not “for the flowery way that

leads to the broad

gate and the great fire” (cf. Matt. 7:13-14). These biblical allusions

came

together easily for Shakespeare, because they are all near one another

in

Southwell’s Epistle of Comfort: “grace”;

“Nabuchodonozor’s

image”; “the prince of darcknesse

. . . the princes and

powers . . . of the worlde of this darcknesse”;

“lowe is our waye

. . . to heaven. . . . the wide waye . . . onlye

leadeth to perdition. .

. . The path to heaven is narrowe” (EC,

52r; 54r;

43v, 49v; 52v-53r).[19]

The Epistle may even help to explain how Lavatch

got his name. After writing

again of Nebuchadnezzar and the “narrowe . . . waye, that leadeth to

lyfe” (EC,

149v, 146v), Southwell

says of Catholic martyrs: “Well

may they be called, the neat or kine of the church

. . . , feeding uppon grasse and wilde hearbes

unfitt for mans

eatinge [to] turne them into

sweete mylke . . . for the benefitt of mankinde” (152r).

Lavatch the

Cow (“neat,” “kine,” “la vache”) and self-styled

“prophet” (AW

1.3.58), who claims to have little skill in “grass” or in “grace”

(which were

phonetically the same) and is averse to suffering in the “flesh” for

any kind

of principle (AW 1.3.29), feeds only for himself.

Thus from Southwell’s

perspective he would be an anti-martyr, with a name that suits him with

an apt

irony.[20] This apparent

cacophony of miscellaneous

memories, when added to the other elements that have made All’s

Well

into a “problem play”--its ambiguous tone, its unusual blend of generic

conventions, its perplexing ethic--turns the drama into an

extraordinary

challenge. Shakespeare, if writing it especially, did not write it

exclusively,

for an audience of one. Yet no audience could have been aware of all of

its

subterranean echoes. “All’s well

that ends well” is a maxim

often embraced by those who feel the need to forget the failure that

precedes

success, or the pain through which happiness is achieved, but who may

in fact

have to live in an imperfect oblivion. The play’s psychological realism

competes on such even terms with its folk-tale elements that it is not

easy for

an audience to forget the character flaws in the married couple that

might

qualify (though without wholly undermining) a happy ending. If all is well, it could

have been and may

yet be better, and may be worse. This is a truth of which “All’s well that ends well”:

lurking behind

this aphorism is another one, “the end justifies the means,” which can

embody a

philosophy of ethical adventurousness or of ethical opportunism. Does

Shakespeare accept or renounce such a principle in his play?[21]

Helena lies and manipulates her way to a success that is hard to

begrudge her,

especially if she is as “good” as almost everyone in the play believes,

and if

she is as “good for” Bertram as he seems finally, if abruptly, to

recognize.[22]

And

yet Helena herself does not “justify” her actions very well.

“Ambitious” in her

love (AW 3.4.5), she believes that she deserves

Bertram: “Who ever

strove / To show her merit, that did miss her love?” (AW

1.1.226-27).

She gains a husband, however, not by “showing” her worth but by using

the

coercive power of a King, in a ploy whose justice she never questions.

She

regains Bertram by lying about her death, by persuading a priest to do

the

same, and by resorting to the bed-trick in which she substitutes

herself for

the woman her husband thought he had seduced. Let us assay our plot, which if it speed, Is wicked meaning in a lawful deed, And lawful meaning in a lawful act, Where both not sin, and yet a sinful fact. (AW 3.7.44-47) Bertram’s

intention (“meaning”) may be

“wicked” yet “lawful,” since he intends adultery but in having

intercourse with

his wife does not physically commit it. The civil law is concerned here

with

behavior, not intentions (a point of importance in the much more richly

casuistical Measure for Measure). Religious law,

however, does consider

intention in defining the morality of an act. Adultery may be committed

in the

“heart” alone (Matt. 5:28-29), and Bertram is guilty of it. It is not

true,

then, that “both” do “not sin.” Indeed, a theologian might convict If faults

matter in the play, however, they

do not matter utterly. The unsavory melancholy and cynicism of the

clown is

tolerated by the countess, who does not like him but keeps him in her

employ.

Though “honesty be no puritan,” Lavatch insists, it will “do no hurt”;

pure

perfection, he implies, would do hurt, and a less

radical goodness does

well to temporize with the ideal, as even proud puritans do with the

authorities over the “surplice” (AW 1.3.93-95). No

one gainsays him or

provides a confuting example. Higher on the scale of iniquity is

Parolles, who

is shallow, posturing, deceitful, and corrupting, guilty of personal

and

political treason. He raises laughs, unintentionally, but has little

wit to

cover his multitude of sins. Yet even the Lord Dumaine, whom he

slanders, says

with a generosity at least partially ingenuous that he begins to “love”

Parolles,” and finds that “rarity redeems him” (AW

4.3.262, 274). What

saves Parolles, in fact, is his stripping down to essentials: “Simply

the thing

I am / Shall make me live” (AW 4.3.333-34). He is

“simply” a fool, but

has to be even more simply a man to be so, and Lafew’s contemptuous

anger

toward him after the knave’s humiliation changes to pity: “though you

are a

fool and a knave, you shall eat” (AW 5.2.53-54). No one in the

play but Helena herself

believes that she needs to be forgiven for anything. She herself feels

remorse

when she learns that Bertram has fled from “the dark house and the

detested

wife” to a war that may kill him: “Whoever shoots at him, I set him

there”

(2.3.292, 3.2.90-129). Her sense of guilt, however, does not survive

the

penitential pilgrimage that she makes, perhaps not to Compostela as she

had

announced, but certainly to Bertram’s a man noble without generosity, and young

without truth; who marries

Helen as a coward, and leaves her as a profligate: when she is dead by

his

unkindness, sneaks home to a second marriage, is accused by a woman

whom he has

wronged, defends himself by falsehood, and is dismissed to happiness.

A “typical”

critic’s grievances against I cannot reconcile my heart to Helen: a woman who pursues and captures, not once but twice, a man who doesn’t want her; uses trickery in order to force herself on him sexually; and finally consolidates her hold on her husband to a chorus of universal approbation.[24] A sympathetic

actress may considerably

lessen the severity of such a judgment (Angela Down managed to do so in

Elijah

Moshinsky’s BBC production) but cannot suppress it entirely. All’s Well may be read,

however, as though Shakespeare, characteristically,

wishes in this play to solicit mercy especially

when granting it seems

most shocking to a conventional or complacent moral sense, as in the

case of

Bertram. The playwright changes Boccaccio’s Beltramo into his own

Bertram in

ways that make the young count of Rossillion seem unforgiveable. There

is

nothing in the Decameron like Bertram’s ugly

descent, in the play’s

final scene, into suave arrogance, false remorse, self-interested

ingratiation,

desperate lying, and slanderous abuse. And yet Bertram is “dismissed

into

happiness” anyway--or rather, into the “hope” of happiness, since the

play’s

ending is deliberately made to appear provisional: “All yet

seems well,”

says the King, “and if it end so meet, / The bitter

past, more welcome

is the sweet” (5.3.333-34; emphasis added). Bertram’s words of

repentance are

terse and few; he does not say or do enough to conform to the

stereotype of the

prodigal who is forgiven because of his ostentatious compunction.[25]

He

is forgiven not so much because of what he has become but because of

what he

may, but will not necessarily, be; and thus he is shown the most

powerful (some

would say, irresponsible) kind of mercy. The ending of All’s

Well need

not, then, reveal an inept Shakespeare, hastily closing down a play

that was

failing, or a cynical Shakespeare, debunking comic formulas on which he

had

relied for too long,[26]

but

a radical Shakespeare, advancing a long-held and deeply felt ethic.

This moral

vision was embodied not only in the playwright’s “comedies of

forgiveness”--of

which Measure for Measure with all of its

resemblances to All’s Well

in situation and theme would prove the most notable example--but in Venus

and Adonis,[27]

a clear prototype of All’s

Well and the first poem that

Shakespeare dedicated to the earl of In All’s

Well, however, the future

is more an hypothesis than a vision, and it cannot escape its origins.

As

Helena and Bertram, the new generation, strain toward independence,

they are

tied to the past that created them. Helena claims to have forgotten her

father,

but her ambition would have come to nothing without the gift of

knowledge she

had received from him; and that ambition, of course, is nothing else

than to

marry the man presented to her by her childhood. She is a young (not a

“new”)

woman, intelligent and aggressive, who makes use of the “old”

institution of

wardship to achieve her great desire, and is comforted and abetted by

her

elders. The King is indebted to the young, but he is suspicious of new

ways

that he believes lack the authentic nobility of the old ones, which was

evident

in the greatness of the dead count of Rossillion. If Bertram is to be

saved, it

is by being brought back into conformity with the ideals of his father

and

mother, and thus made worthy of the “blood” he has inherited. Such is

the power

of the past in Shakespeare’s story, and its influence makes “all end

well,” if

the play provides an acceptable meaning for each of these terms. As we have

seen, however, the tale itself

is also an accumulation of memories woven like a “mingled yarn” out of

a

history that has left traces of itself in literature. These copious

vestiges

are of several kinds. Some are surely the inevitable repetitions of a

poet who

cannot forget all that he has said when he ventures to say something

new. Some

seem deliberately to recreate the “Shakespeare” who wrote works “for”

Southampton: poems or plays that fulfilled in a general way a promise

to

dedicate “all” to a patron and friend; or, like Venus and

Adonis, Lucrece, Julius

Caesar, Hamlet,

and Sonnet 107, that spoke to

Southampton’s situation or state of mind. Others are reminiscences of

Robert

Southwell, the dead Jesuit whose legacy Shakespeare held onto

tenaciously, in

spite of the many reasons he had to resist or forswear it. What is the

power of

this kind of “past” as it exhibits itself in a play with special

meaning for The past,

insofar as it had not vanished,

had become what The

past-made-present was also Robert

Southwell, spokesman for the Old Faith that would never cease to

importune. The

Jesuit cousin of Shakespeare and Southampton had challenged both men

long

before All’s Well was written. Shakespeare

inscribed the Jesuit’s words

on his “heart’s table” and would not erase them. Southwell was present

in Venus

and Adonis and Lucrece when those poems

ushered The other part

of Southwell’s message that

the play recalled was the uncompromising commandment, “seeke not . . .

good by

evill” (EC, 53r). As already

suggested, All’s Well that

Ends Well tests the principle that the end may justify the

means and stops

short of endorsing it. Shakespeare emphasizes forgiveness rather than

acquittal. And yet, if forgiveness is granted generously and

promiscuously, the

rigorous axiom that ends may not justify means seems mitigated. When

forgiveness is the end, who is to say that all does not end well? Not

Robert

Southwell himself.

[2]. See Kerrigan,

ed., Shakespeare: The

Sonnets and a Lover’s Complaint, 313-20; Evans, ed., The

Sonnets,

216-17; Duncan-Jones, ed., Shakespeare’s Sonnets,

21-24, 324.

[3]. If “my true

love” is interpreted as “the

one whom I love” (the person who “looks fresh”), the “confined doom”

would mean

the loved one’s imprisonment. In 1603-4, this would more likely refer

to

[4]. Evans (217)

notes other reminiscences of Hamlet

in the sonnet, concentrated in the first scene: for example, “the most

high and

palmy state” (1.1.113; cf. “this most balmy time” [9]); “the moist star

. . . /

Was sick almost to eclipse” (1.1.118-20; cf. “mortal moon hath her

eclipse

endur’d” [5]); “the like precurse of fear’d events, / As harbingers

preceding

still the fates / And the prologue of the omen coming on” (1.1.121-23:

cf.

“presage” [6], “fears . . . [of] things to come” [1-2], “prophetic

soul” and

“augurs” [1,6]).

[5]. MacDonald P.

Jackson’s recent stylometric

studies of the Sonnets, building upon the work of other scholars, has

led him

to the conclusion that most of the poems were written later than is

usually

assumed, “at least . . . three years” after the period 1593-1596. This

fact,

The Sonnets, whatever their dates, should not be read naively. It is hard to imagine how either the countess of See [6]. Dating All’s

Well is difficult,

but the more persuasively argued educated guesses place it ca. 1603-4,

preceding Measure for Measure. Stanley Wells and

Gary Taylor believe,

mainly on the basis of stylistic tests, that All’s Well

is the later

play, and suggest 1604-5 (A Textual Companion,

126-27).

[7]. Akrigg, Southampton,

256. In Romeo

and Juliet, the “county”

[8]. Akrigg,

[9]. Akrigg, Southampton,

50-51.

[10]. Akrigg,

[11]. Akrigg, Southampton,

134-35.

[12]. On the

Touchstone-Lavatch parallels, see

Price, The Unfortunate Comedy, 147, 153.

[13]. All’s

Well that Ends Well, 30. See

also, among other studies, Bradbrook, “Virtue is the True Nobility: A

Study of

the Structure of All’s Well that Ends Well,” 290;

Warren, “Why Does It

End Well?

[14]. Hamlet

2.2.529-30, All’s Well

2.2.50-56; Hamlet 5.2.147-48, All’s Well

2.3.59; Ham

1.3.115, All’s Well 4.1.90; Hamlet

2.2.238, All’s Well

4.3.267; Hamlet 3.4.77, All’s Well

4.3.118; Hamlet

3.2.155-58, All’s Well 2.1.161-167; Hamlet

1.3.50, All’s Well

4.5.54-55; All’s Well 2.3.1-3, Hamlet

1.5.166-67. Cf. also “the table of my memory”

(Hamlet

1.5.98) and “draw . . . In our heart’s

table” (All’s Well 1.1.93-95); “man

and wife is one flesh”

(Hamlet 4.3.52) and “He that comforts my

wife is the cherisher of my flesh

and blood” (All’s Well

1.3.44-45); “in the cap of youth” (Hamlet

4.7.77) and “in the cap of the time”

(All’s Well 2.1.53); “when honor’s

at the stake” (Hamlet 4.4.56) and “honor’s at the stake” (All’s Well

2.3.149); “take him in the purging of his soul”

(Hamlet

3.3.85) and “took him at’s prayers” (All’s

Well 2.5.41-42); “the woundless air”

(Hamlet 4.1.44) and “the

still-piecing [i.e., “constantly closing itself up again] air” (All’s Well

3.2.110 and Riverside

note); “some enterprise / That hath a stomach in it” (Hamlet

1.1.99-100) and “you have a stomach, to’t . .

. , in the enterprise” (All’s Well

3.6.64-67).

[15]. See above,

Chapter 2, note 31.

[16]. This part of

the Funeral Teares

Shakespeare had recalled in some detail in composing A

Midsummer Night’s

Dream 5.1.90-105. See Chapter 1, above.

[17]. “The

still-[piecing] air” recalls a line

from the Wisdom of Solomon, 5.12: “like an arrowe . . . whose tracte

the ayre

sodaynlye closeth”--which Southwell quotes in EC,

117r.

[18]. In the

stichomythic exchange between

Lafew and Parolles that follows All’s Well 2.3.6,

the textual parallels

continue.

All’s

Well 2.3

EC

12: 88v: learned and authentic fellows grave and authenticall authors 20: 80v: a novelty to the world to the worldes . . . noveltyes 23-24: 88v, 93v: a heavenly effect in an earthly actor God the onlye author of these supernatural effectes; chiefe actour [19]. On these and

other allusions to the bible

in All’s Well, see Shaheen, Biblical

References in Shakespeare’s

Plays. Shaheen notes that among all of the Tudor and Stuart

translations,

only the Catholic Rheims (like Southwell) has the “narrow” gate, all

others

reading “straite” (279). The “flowery” way to perdition (as also in Hamlet

1.3.47-50 and Macbeth 2.3.18-19) is extra-biblical;

but note Southwell’s

“If the way had bene besett . . . with flowers” (EC,

54r).

[20]. In the Humble

Supplication,

Southwell turns martyr-quellers into kine and the

martyrs into their

food: “We are made . . . common forage for all hungry Cattle” (see

43-44).

Of many other verbal parallels between the play and Southwell’s works, the following might be noted:

All’s

Well

Southwell

1.3.25-6: “The Complaint of the B. Virgin . . .,” 64: barnes are blessings blessed barne 1.3.217: EC, 29v: But riddle-like lives sweetly where she dies! Sampsons ridle . . .out of the stronge issued sweetnesse 2.1.171: HS, 41: a divulged shame devulged . . . shame 2.3.44: EC, 29r: Mort du vinaigre by his [Christ’s] vinagre and gall . . . , by his . . .death 2.3.163: EC, 129v, 131r, : staggers and the careless lapse carelesse . . . lapsed . . . stagger 2.3.195-99: MMFT, 25r: Count’s master is of another style . . . so many proofes would persuade thee I must tell thee, sirrah, I write man; to . . . unworthy of that stile, and we can which title age cannot bring thee afford thee no better title then a Woman 4.3.71: “Times goe by turnes,” 10: The web of our life is of a mingled yarn [Fortune’s] Loome doth weave the fine and coursest webbe 4.3.90: MMFT, 24v: parcels of dispatch parcell . . . dispatcheth 4.3.182-86: HS, 33: answer to the particular of the Interrogatories . . . answer . . . Some are inter’gatories . . . he was whipt whipped [21]. Susan Snyder

examines the implications of

every word in the play’s title, including the suggestion that end

justifies

means. See the Introduction to her edition of All’s Well,

49-51.

[22]. On the

disputes over Helena’s character

and what she finally does or does not deserve, see the critical history

of the

play given in Price, The Unfortunate Comedy, 75-129.

[23]. Maurice Hunt

believes that Shakespeare

had Helena make a pilgrimage first to Spain (where she “persuades the

priest of

St. Jaques to write Bertram of her ‘death,’”) and has her discover

Bertram by

accident later as she wanders into Florence, a place now associated

with her

husband, without expecting to

find him

there (Shakespeare’s Religious Allusiveness, 59).

Such an interpretation

makes it difficult to understand why

[24]. Snyder, ed., All’s

Well that Ends Well,

27-30

[25]. Robert Gans

Hunter’s study, Shakespeare

and the Comedy of Forgiveness, insists too strongly that the

quality of

mercy is constrained by the sinner’s need to conform to a penitential

formula.

Shakespeare is often faulted for giving Bertram, as well as Angelo in Measure

for Measure, too little to say to make repentance convincing.

Are, however,

all the rhetorically more copious penitents of Marston’s Malcontent

(with which Measure for Measure is often compared)

more, or less

plausible in their conversions?

[26]. Anne Barton,

in her Introduction to Measure

for Measure in the Riverside Shakespeare,

suggests that at this

stage in his career, Shakespeare seems to have become “disillusioned

with that

art of comedy which, in the past, had served him so well.”

[27]. See Klause,

“Venus and Adonis: Can We

Forgive Them?”

|

|||||||||||||

| Copyright © John Klause 2013. |